Paul Clayton

| Track | Album |

|---|---|

| Polly Von | Bay State Ballads |

| The Seaman's Grave | Bay State Ballads |

| The Twa Sisters | Folk Ballads of the English Speaking World |

| Old Joe Clark | Dulcimer Songs and Solos |

| Shady Grove | Dulcimer Songs and Solos |

| Go Down You Blood Red Roses | Whaling and Sailing Songs ... |

| Jesse James | Wanted For Murder |

| Tom Dula | Bloody Ballads |

| Pay Day At Coal Creek | Folk Singer! |

| Gotta Travel On | Folk Singer! |

Contributor: Andrew Shields

If Paul Clayton is remembered today, it is primarily for three reasons. The first of these is the fact that he was an important early mentor to a number of the key figures in the Greenwich Village scene in the early 1960s. This group of Clayton’s friends and protégés included such important artists as Dave Van Ronk, Bob Dylan and Laura Nyro. The second reason is that Bob Dylan’s great early song, Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright was based (in part at least) on Clayton’s earlier composition, Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons (When I’m Gone). Dylan’s use of Clayton’s song in this way created some controversy at the time and eventually formed the basis of a legal action, which was settled out of court. The third reason is the fact that it has been alleged that both Dylan’s It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue and Joni Mitchell’s Blue were written about Clayton, although neither of the artists involved has ever confirmed this.

It has also been the case, however, that Clayton’s closeness to Dylan, in particular, has led to his being seen primarily as source of material for the latter, rather than an artist in his own right. This has obscured the fact that Clayton was an important figure in the Folk Revival well before Dylan arrived in New York. Indeed, he can be seen as a key transitional figure in that movement, a link between the older generation represented by Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, and the younger singer-songwriters of late 1960s and early 1970s. He was also an important collector of folk songs and among the artists whom he discovered, or made field recordings by, were the great guitarist, Etta Baker (whose finger-picking style was to have a huge influence on the Greenwich Village ‘folkies’ of the early 1960s), and the bluesman, Pink Anderson.

Clayton was also a talented songwriter and had a hand in writing one of the most enduring songs of the Folk Revival, Gotta Travel On. It has subsequently been recorded by everyone from Billy Grammar (who had a major hit with it in 1959) through to the Kingston Trio, Bill Monroe, Bob Dylan, Jimmie Dale Gilmore and, most recently, Neil Young, who included the song on his 2012 album, Americana. I have included Clayton’s own version from his last album. Along with these other accomplishments, Clayton was also a fine singer and, at his best, a superb interpreter of folk songs.

Because Clayton recorded so much in such a short space of time – some 17 albums between 1954 and 1961 – it is perhaps unsurprising that the quality of his recorded work is variable. At times, again unsurprisingly, the arrangements on his records sometimes sound dated and he was not completely immune from some of the faults of the early Folk Revivalists. These faults included the adoption of a kind of arch coyness at times which was, perhaps, derived from some of those who were at the poppier end of the early Revival (examples would be acts like Burl Ives and The Weavers). However, at his best, Clayton easily surmounted the limitations imposed by the folk conventions of his day. Indeed, his singing had a peculiarly timeless quality to it (a quality achieved by only the very best folk singers) and this means that the best of his work still stands up today, in a way which that of some of his more feted contemporaries does not.

One of the things which almost all of Clayton’s contemporaries have also drawn attention to is his extraordinary knowledge of folk music. This came in part from his academic background (he had studied it to the postgraduate level at the University of Virginia) but it also reflected his deep attachment to, and respect for, the music. As a result, Clayton’s records provide a quarry of great songs, one which, up to now, has largely been left unmined. Also, even when he sang relatively well known songs, Clayton had an unusual knack for finding variant and often slightly quirky versions of them which kept them interesting.

Paul Clayton’s recordings also reflect the eclecticism of his musical tastes, mixing musical genres in a way which shows little of the purism which was favoured by some other Revivalists. A typical Clayton record of this time could, for example, include a Child ballad, an Irish or Scottish broadside song, a sea shanty, an Appalachian song or instrumental, a murder ballad from the African American tradition, and so on. In this respect, at least, it could be argued that Dylan’s two great albums of folk covers of the early 1990s, Good As I Been To You and World Gone Wrong follow the template which Clayton set at this time.

My first choice here is Clayton’s version of the great folk ballad, Polly Von, which it has been claimed has Irish origins. Bob Dylan was later to record a fine, but as yet unreleased, version of the song using the variant title of Polly Vaughan with David Bromberg and his band. Lyrically at least, that version was very close to Clayton’s version and it is probable that Dylan first heard the song through him. In Chronicles Dylan has described Clayton as being both ‘forlorn and melancholic’ and it was the case that he had a particularly effective way with a song of the same kind. This can be seen from my second choice here, The Seaman’s Grave, a ballad about a death at sea which Clayton delivers with a beautiful economy and restraint. Like many of his recordings, it is also a ‘grower’ which reflects his subtlety and the good taste which was one of his hallmarks as an artist.

My third choice is a Child Ballad, The Twa Sisters (or The Two Sisters), and, in my opinion, Clayton’s is the definitive version of the song. It also shows Clayton’s complete mastery of the long narrative song. He was later to teach Dylan a variant version which included a repeated chorus of “Turn, turn to the rain and the wind” which the latter went on to use as the basis for his own, Percy’s Song. Although Clayton performed this variant on a number of occasions in concert (most notably at Newport in 1963), he never recorded it. The Irish group Altan have, however, recorded a very similar version of the song on their album, Local Ground, which was released in 2005.

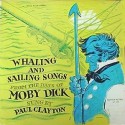

There are two Clayton albums which rank with the very best of those produced during the Folk Revival. These are Dulcimer Songs and Solos, from which I have included two of the best tracks here. The second is his classic album of sea shanties, Whaling and Sailing Songs from The Days of Moby Dick, which is widely acknowledged as one of the best recordings in that genre. Clayton’s expertise in the area owed a good deal to his childhood in New Bedford and to the influence of his grandfather, who had collected a large number of songs from the whalers and dockworkers in the town himself. The entire album is suffused with Clayton’s obvious affinity with and respect for this material as the version of Go Down You Blood Red Roses, which I have included here, clearly demonstrates.

My final choices include songs from Paul Clayton’s two collections of ‘murder ballads’ and two tracks from his final album, Folk Singer!. The first of these is Clayton’s excellent version of the old Western ballad, Jesse James, with its memorable chorus of “I wonder where my poor old Jessie’s gone”, which he may well have written himself. This video footage of Clayton performing the song at the 1963 Newport Folk Festival has only just surfaced. It was unearthed by the team behind the play about Clayton – Larry Mollin’s “Serarch: Paul Clayton” – which has just concluded its run at the Triad theatre in New York. Up until its appearance, it was widely believed that no such video material existed and, in consequence, this is a very important find for the history of the folk revival.

The second is his fine version of Tom Dula, one of the first ever to be recorded and, in my opinion, far superior to the Kingston Trio’s later version. However, it was their recording which was to become a crossover hit and, indeed, one of the defining songs of the Revival era. Pay Day At Coal Creek is a classic banjo tune originally recorded by one of that instrument’s greatest exponents, Pete Steele. Clayton does this song full justice and, in my view, it ranks as one of his best vocal performances ever.

Although he died young, his many achievements as a scholar, musician, collector and singer meant that he deserved far better than the obscurity that he was to fall into for many years after his death. Thankfully, however, the publication of Bob Colman’s fine biography of him in 2008 and the inclusion of a character that is (very loosely) based on him in the Coen brothers’ recent movie, Inside Llewyn Davis, seem to have inspired a well-deserved revival of interest in Paul Clayton’s work.

Paul Clayton biography (iTunes)

TopperPost #228

This is a great post of a fascinating artist. Andrew, is the character that is loosely based on Clayton in the film Troy Nelson? Would it be fair to say that Dylan would have his considered his “borrowing” of lyrics and melodies being consistent with what had always gone on in folk music? Girl From the North Country is another example. That said, within that small folk community between 60-62 Bob must have really been putting people off with his appropriations, what with Clayton’s tune and of course more famously Dylan’s lift of Van Ronk’s arrangement of House of the Rising Son. Of course there is further controversy with the Animals when Alan Price takes off the arrangement royalties, much to Burdon’s chagrin, but as Van Ronk says in his book, its all his arrangement, should have been his royalties.

Thanks for a great piece. I loved the line “the adoption of a kind of arch coyness” which indeed extends to The Weavers and many others. You could do a good double CD pairing Bob Dylan with the songs he (allegedly) lifted, and Dominic Behan called him a “plagiarist and a thief” over The Patriot Game, though that in turn was adapted from The Merry Month of May. Then you have Restless Farewell and The Parting Glass. On the recent release of an early radio show, Bob Dylan is quite open in the interviews about lifting songs.

I researched Gotta Travel On a few years ago. What’s interesting is that it sounds as if it’s been around forever and ever. Billy Grammer’s hit version credits it to Paul Clayton. The Bob Dylan cover on “Self Portrait” credits it to (Paul Clayton / Larry Erlich /David Lazar /Tom Six). Dylan was taped singing it in 1960 in Minnesotta well before he met Clayton. Bill Monroe recorded it and just credited Clayton. When Johnny Kidd & The Pirates covered it they went for “Trad. Arranged Kidd.” If it truly was “Trad” then, judging by the rest of Self-Portrait, Dylan would have claimed it, or done a “Trad. Arr.” though Clayton was a friend. The copyright info on lyrics has the four person credit. The most outrageous Dylan claim on Self-Portrait was It Hurts Me Too. Both are missing from “Another Self Portrait.”

(Glenn watch out for the forthcoming Animals Toppermost which has more on House of The Rising Sun).

.

Thanks for these comments. There is some recent research on ‘Gotta Travel On’ by Jaan Kolk which suggests that it is (at least, in part) based on Ollie Martin’s ‘Police And High Sheriff Come Ridin’ Down’. There is a youtube clip of it here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YUXhxh7Agv0

Its provenance is also discussed in Bob Coltman’s fine biography. Clayton seems to have put his own songs together from a variety of sources – a patchwork method which, funnily enough, is close to the way that Dylan himself works today…

Glenn – the character based on Clayton (essentially in appearance only) is Jim played by Justin Timberlake… As Anne-Margaret Daniel points out in the Huffington Post ‘rather appallingly’ Timberlake has referred to Clayton in interviews as ‘an Irish folk singer”…

Personally I think Dylan’s failure to give Clayton some credit for ‘Don’t Think Twice’ was a shame, especially as he had been a friend and a mentor and could have done with the money. Can be justified on the grounds of the ‘folk process’ , I suppose, but not an edifying episode…

Many thanks for the Ollis Martin link … the tune of Gotta Travel On is there, and I thought the words, though totally different, were great. There were these great folk archivists researching things and finding songs … Jon Boden and Fay Hield are the 2014 British equivalent, though they always trace everything they know of the sources.