Bob Luman

| Track | Single |

|---|---|

| Stranger Than Fiction | unissued at the time |

| All Night Long | Imperial X8311 |

| Wild Eyed Woman | unissued at the time |

| This Is The Night | unissued at the time |

| Red Hot | Imperial X8313 |

| Make Up Your Mind, Baby | unissued version |

| Guitar Picker (feat. Eddie Cochran) | bootleg believed recorded 1958 |

| Loretta | unissued at the time |

| You're Like A Stranger In My Arms | unissued at the time |

| Let's Think About Living | Warner Bros 5172 |

Bob Luman

Contributor: Dave Stephens

In every other song that I’ve heard lately

Some fellow gets shot

And his baby and his best friend both die with him

As likely as not

In my mind, Bob Luman falls between two stools. On the one hand he was a One Hit Wonder with Let’s Think About Living, a blow-in from Nashville and the kind of thing we later called a country crossover, a small but select breed of record that became popular in the late fifties and early-to-mid sixties. We were both right and wrong about that – more later – but it didn’t matter; while the record title might have suggested a rather earnest or new-wavey paean to positivity, the song itself was from that let’s-have-a-chuckle-school of country music and the way the then unknown Bob sang it suggested he might just about have heard of rockabilly. So, a welcome performance in the late summer of 1960 when elsewhere rock and roll in its initial incarnation seemed to be dying on its feet.

The “then unknown Bob” as I referred to him had certainly heard of rockabilly. During the revival of the genre in the seventies when record labels competed with each other to get compilation albums of such music out to an eager audience, fans like yours truly realised that we’d missed out on the early career of Mr Luman. His Imperial, Capitol and even the first Warner Brothers single hadn’t seen release in the UK. Those records included his version of the rockabilly classic Red Hot, originally recorded by Billy “The Kid” Emerson on Sun in 1955 and then covered by Billy Lee Riley in 1957, also on Sun – Sam Phillips liked his artists recording songs on which he had copyright. Both the vocal from Bob and the general atmosphere of primitivism put his record, from later on in ’57, on at least the same level as Billy Lee while the guitar work from a very young James Burton elevated the disc onto a pedestal of its very own.

For whatever reason though, the Luman name isn’t among the first to come to mind when I think rockabilly. Maybe that’s because of the relatively small number of singles/sides that he recorded in the idiom before moving, or being moved, onto other things. However, that wasn’t unusual, very few artists outside of Carl Perkins and Gene Vincent released more than a handful of singles that could be said to be truly in the genre and there was a reason for that: very few rockabilly records sold in sufficient quantities to justify the investment by the relevant record label.

Mind you, real rockabilly fanatics will have dug underneath the American single releases from Luman in the fifties and discovered further treasures. The label, Rollin’ Rock Records was founded in 1970 by a gent called Ronnie (sometimes Ronny) Weiser. Its raison d’être was all things rockabilly so it was hardly a surprise that it was this label which unearthed and released tracks made by Luman prior to his signing by Imperial. With the arguable exception of one slowie, the six tracks issued were solid rockabilly. The Rollin’ Rock releases took place in 1974. Since then, the Luman rockabilly trove has grown considerably via Bear Family getting access to tracks that didn’t see release from his official sessions at Imperial etc. plus further unofficial sessions. With the advent of the internet this information is now in the public domain via sites like RCS (Rockin’ Country Style) and Praguefrank. All of which confirms that Bob Luman recorded more than a handful of tracks that could be called rockabilly and the quality of these should definitely make his a name to be remembered.

That first session for Jim Shell in Dallas is as good a place to start in on the music as any. The Mac Curtis band, which comprised the Galbraith brothers on guitar and bass plus Dick Powell on drums, provides a highly competent backing if not quite as fiery as the James Burton era outfit; the songs which come mainly from Shell himself are perfectly good rockabilly vehicles; and Luman on lead is at least as good as Mr Curtis on vocal. If I’m slightly grudging on praise for Bob in that last statement, one should bear in mind that these were his first ever tracks performed with a pick-up band and with songs he had to learn for the session. I’ve selected Stranger Than Fiction as a representative of the grouping but really I could have gone for almost any of the cuts, the overall quality was that good.

Note that the lead photo on this clip is of Bob with his first official band, the Shadows. Whilst slightly misleading, I decided to stick with this clip since it’s a rare photo of the band with the ridiculously young looking James Burton on guitar.

All of which segues very neatly to the first tracks recorded with the Shadows – Burton lead guitar, with James Kirkland (bass) and Butch White (drums) plus, sometimes, Gene Carr on piano. The initial tracks cut by the band were, once again, unofficial in that they were intended for release but it didn’t happen – see also Footnotes. A couple of tracks, That’s Allright (not the Presley number) and Hello Baby were repeats of songs cut at the Jim Shell session. A quick listen to That’s Allright tells us that the new lad on guitar whilst sticking largely to the Scotty Moore playbook, demonstrated more edge than Jimmy Galbraith. The tantalisingly short, No Use In Lying – strongly suggestive of someone forgetting to put the record switch to ‘on’ till half way through – might well have been the best track from the session. The other tracks recorded were instrumentals.

The first single cut by Bob & the Shadows for Imperial, All Night Long in Summer ’57, was a strong rocker with touches of melody, and, with more oomph in terms of promotion, might have seen some chart action. The basic rockabilly approach had been modified to incorporate an effective chordal form of riff from Burton which he varied with fast single string runs. If you turned over All Night Long you would have found Bob’s original version of Red Cadillac And A Black Moustache, a number which might be better known to some via the version from Warren Smith cut in the same year but not released until 1973 (and then praised as a previously undiscovered nugget). Anyone coming across the Luman ‘version’ after Warren’s might have viewed it as a tribute to a fellow rocker. Such ‘tributes’ to rockers would appear to have continued with a take on Buddy Holly’s Blue Days, Black Nights which stayed in the can until decades later. One of those songs which blurred the edges between rockabilly and country, this might have been a pointer to Bob’s future.

His best ‘tribute’ disc though, just had to be Red Hot which appeared on the flip of single #2. Which is all very well but for the fact that, in terms of sessions, I have managed to get ahead of myself. According to the PragueFrank Bob Luman discography, the very first Imperial session that yielded All Night Long also produced Wild Eyed Woman, another fine rocker which languished in the can. About as close to blues as Bob and the guys got, this track was blessed with the sort of feel one rarely heard from white rockers:

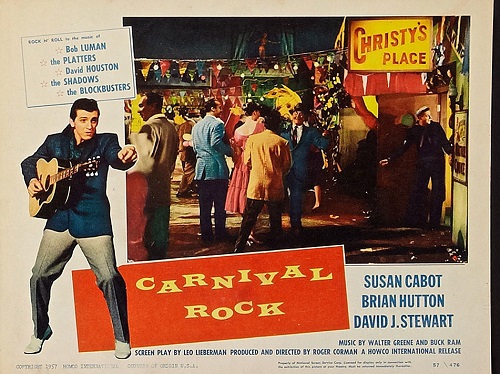

It was even more strange that This Is The Night from session #2 for Imperial didn’t see single release. I say that because Bob and the Shadows were featured in Roger Corman’s 1957 movie Carnival Rock playing that song, so one might have expected a release and some plugging.

Note the ‘17 Years Old’ which the uploader plops onto the screen for the Burton break. I should add that if you clicked on All Night Long earlier you would have seen Bob & the Shadows perform their other number from the film.

An element of taming, or softening, might have already started to happen to Bob and the band’s output. It took a couple of sessions to nail down Make Up Your Mind, Baby. The version that eventually saw release sounded like this which was perfectly acceptable but lacking somewhat in wildness quotient. You couldn’t say that about one of the alternates which stayed in a rack somewhere until Bear Family found it. The performance could be from a different band entirely. This is the track as recorded in October ’57. James Burton is absolutely all over it. Indeed, it’s something of a tour-de-force; it might even be called his swansong since he was to leave Luman and join Ricky Nelson at the tail end of that year. Needless to say, it’s the alternate which is my selection (see further comment on these tracks in the Footnotes).

That Luman hadn’t stopped rocking is confirmed by a bootleg single which has Bob Luman and the Shadows on the A-side with This Is The Night, and “Bob Luman Feat Eddie Cochran” on the flip with Guitar Picker. And that flip isn’t just a throwaway instrumental, it’s a solid rocker with real lyrics even if, thematically, it was the sort of story that we’d heard before. A sentence on the sleeve notes to the Bear Family set Bob Rocks, sums up the nature of and rationale behind this track: “In the meantime he’d cut a demo of the exquisite ‘Guitar Picker’ with Eddie Cochran and Fred Carter Jnr. on axe duty, but it was a million miles away from the glossy, commercial sound of his Capitol sides”.

As Trevor Cajiao, the man who wrote those sleeve notes stated, Bob’s next move was to Capitol and his first release for the label, I Know My Baby Cares/Try Me was in line with Trevor’s view on the Capitol approach. He was pretty well without a band at this juncture which might explain why Capitol surrounded him with a load of studio cats. The sound was roughly akin to that achieved by the label and largely similar studio guys on Gene Vincent’s 1960 set Crazy Times though without some of the highs in that set. The A-side was not badly done but poppy; the flip was ersatz rock‘n’roll with some similarity to certain Bobby Darin tracks like Queen Of The Hop. That said, I kind of like it but not enough to make it a selection.

In June ’59. Bob recorded another set of demos in L.A. prior to a move to Warner Brothers. A particularly notable feature about the session was that Roy Buchanan was on guitar and he, and most of the studio team, stuck around for the Warner releases. The other notable feature about the session was the track, Loretta which in its one minute and thirty seconds duration demonstrated with some verve that white rock‘n’roll didn’t have to be about Elvis and those guys down in Memphis.

Buchanan also featured on Buttercup which did see release on Warner. It was arguably the last of the great rockers from Bob and team and only missed out on selection after a lot of heart searching.

Meanwhile, the cache of unissued Luman tracks was growing and this continued into the Warner Brothers era. For me, a major mistake by the label was not issuing You’re Like A Stranger In My Arms which was cut in June ’59. It was a ballad. A jogalong country-inflected ballad, but a ballad just the same. Don’t think that because I haven’t featured ballads or teen pop, they hadn’t featured in Bob’s output up to now. It’s just that I’ve concentrated on what I feel were the strengths of Bob and his band. The A-side of his second Imperial single, Whenever You’re Ready, was almost as good teen pop as you could get; Your Love, the flip of his third single, was a country style ballad, his Capitol debut; I Know My Baby Cares wasn’t short of teen pop trappings plus a Jackie Kelso sax solo but was still something of a grower; My Baby Walks All Over Me was almost straight country with a distinct resemblance to one J Cash; and going right back to that first Imperial session, the unissued Amarillo Blues was a fine, if sentimental, blues. Even before that, nestled within all the rockabilly fervour of the Jim Shell session, there was an aching ballad. Let Her Go was the title, and although the backing was at times clumsy, Bob’s control and expressiveness were noteworthy for someone so new to recording.

But I’ve strayed from “Stranger In My Arms”. I attempted to trace the authorship of the song but I found virtually nothing other than the fact that there’s a host of totally different songs on YT with a near identical title. It’s one of those numbers which has a melody line that manages to wander from expectations but with a flow that’s entirely natural and unforced, all serving to focus attention on the lyrics.

You’re like a stranger in my arms

You’re not the same, your love has gone … it’s gone

In 1976, Bob had heart surgery for a ruptured blood vessel and inevitably months of recuperation followed. The first album he cut after returning to his normal routine was entitled Alive And Well and was produced by his friend and Nashville neighbour, Johnny Cash. Among the numbers it contained were several from Cash including a roaring Get Rhythm plus the Don Gibson classic Sweet Dreams. However, I’d put the spotlight on JC’s I Still Miss Someone as the standout track:

The reader will have spotted a distinct lack of coverage of Bob’s successful country phase in the paragraphs above. That’s not because he didn’t produce lots of fine music during the late sixties and seventies. It’s for Bob himself. Ronnie Weiser was quoted in the introductory para in the Rockabilly Hall Of Fame essay on Bob as saying:

“When I asked Bob Luman in the 1970s, in the middle of the Hippie onslaught and the sugary sissy “Nashville Sound”, when very few Americans even knew what the word “rockabilly” meant, when I asked him: “Bob, do you consider yourself a Country singer or a rockabilly singer??”, Bob Luman roared back, without any hesitation whatsoever:

“R O C K A B I L L Y !!!!”

Country or not, for those readers of a certain age, I’m hoping you’ll be singing along to those immortal lines:

We lost old Marty Robbins

Down in old El Paso a little while back

And now Miss Patti Page or one of them

Is a-wearing black

And Cathy’s Clown has Don and Phil

Where they feel like a-they could die

Seated (l to r): Gordon Terry, Johnny Horton, Bob Luman, Johnny Cash

FOOTNOTES

1. Does the world need another definition of rockabilly? Maybe not but it might be worth posing a question: what did (does?) real rockabilly sound like? For an answer, just go and listen to those five Presley Sun discs, possibly skipping I Don’t Care If The Sun Don’t Shine, You’re A Heartbreaker and I Forgot To Remember To Forget (though the last named could be viewed as the first rockabilly ballad). Elvis Presley, Scotty and Bill to give them the credits that appear on the Sun labels, were the first to capture on record that specific blend of blues and hillbilly plus newer elements including Bill’s slap bass, Scotty’s country licks with edge, and most of all, the sheer attack and understanding of black music that emanated from Elvis himself. There may have been folk out in the sticks in rural Tennessee and elsewhere whose sound approximated to these records but none of them had the clarity and drive that positively oozed out of the Sun grooves.

There’s even an argument for saying that the highly constrained nature of the genre both in its instrumentation which was limited to two guitars and stand-up bass, plus its style which was a subset of blues, itself a genre which operated within constraints, makes one wonder whether records from that plethora of artists who’ve been labelled ‘rockabilly’ and came after Elvis Presley, Scotty and Bill, actually added any value to this new sub-genre. Regardless of value, most of these artists added drums, as indeed did Presley when he moved to RCA; in addition, a piano or sax sometimes appeared, and – horror of horrors – even a vocal group. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with such additions but it doesn’t help with labelling (though it should be remembered that labelling is only there for our own convenience). Unfortunately, such additions to, or dilutions of, the basic rockabilly sound, have often been caused by producers or even label owners in the case of small indies, aiming at a sound that they perceived would be more attractive to teen buyers (and also, it has to be said, to get away from the straitjacket that could be implied by the Presley Sun rockabilly approach). In the process some of the excitement, rawness and roots feeling is almost inevitably lost as visible manufacturing takes over from the impression of a few guys sparking off each other in a studio. Temporarily, rockabilly brought spontaneity into the world of pop music but it was all too brief.

While rockabilly was never a massive commercial success what it did do was influence a whole host of performers and would-be performers – the plethora I referred to earlier. As with most things you could apply the 80/20 rule to the quality of their output and expect a reasonable degree of success. Artists like Gene Vincent, Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison and Ricky Nelson started out in this manner. The majority either moved on or faded away though some, like Charlie Feathers, largely stuck with the genre. Bob Luman wasn’t a big standout rockabilly performer but he made some fine records before surviving his teen pop phase and moving on to (or back to) country.

2. Many of the early rock and R&B artists spent a spell in the US Services, usually on what we would term on this side of the pond, their ‘National Service’. Billy “The Kid” Emerson, who was born in 1925 in Tarpon Springs, Florida, was unusual in that he managed two, firstly during World War II and secondly in ’52/’53. For the latter period – in the US Air Force – he was stationed in Greenville, Mississippi where he met Ike Turner. The Air Force stint over, Billy joined Ike’s band, the Kings of Rhythm. He had already picked up his nickname after a club owner back in Florida had Billy’s then band dress in western clothing for performing.

It was Turner who got Billy in the door at Sun Records in Memphis, and his first single, which paired a couple of self-penned blues ballads, had Ike and others from his band in support. Ike also appeared – quite recognisably – on Billy’s second Sun single, The Woodchuck, a solid slab of novelty R&B which was again self-penned. However, on subsequent records, Billy and Ike parted ways. Most notable among these records were the slow blues When It Rains It Pours and Red Hot. The first of this duo was covered twice by Presley, first at Sun and then at RCA though neither cut was released in a timeframe that was remotely contiguous with its recording date.

Red Hot, of course, is the reason for the presence of this footnote. Originally it was a cheerleader’s chant for Billy’s school football team. Merely substitute “our/your team” for “my/your gal” in the lyrics and you’re part way there:

My gal is red hot

Your gal ain’t doodly squat

Yeah, my gal is red hot

Your gal ain’t doodly squat

Well, she ain’t got no money

But man, she’s a-really got a lot

The repeated second line, “Your gal ain’t doodly squat”, typically sung by members of the backing band, was a common device in forties and fifties jump blues. The same stylistic approach was carried through to the versions of the song from Billy Lee Riley and the Little Green Men, and Bob Luman. And if I was a tad dismissive about the Riley version earlier I probably shouldn’t have been. The relatively unheralded Roland Janes does a great job on guitar and the Luman cut wouldn’t have happened without this model.

Back to Billy Emerson who never really hit any headlines. He moved to Chicago in ’57, recording initially for Vee Jay and then Chess. His song writing skills were also in demand in the Windy City; he sometimes twinned with the great Willie Dixon on songs. In more recent years – according to Wiki, Billy is still with us – he has taken up religion, operating under the name Reverend William R. Emerson.

For a much more detailed view of the influence Ike Turner had on post war blues I strongly recommend the Toppermost from Cal Taylor.

3. It might seem rude to relegate the Bob Luman biography to the footnotes but the good news is that Bob eventually found a second career in country music, with several singles hitting the Country Top Ten in the early seventies and a positive shed load of other records hitting the Country Top 100.

He was born Robert Glynn Luman in 1937 in Blackjack, just outside Nacogdoches, Texas. His father was musical and Bob received his first guitar at the age of 13. At high school he was torn between baseball and music as a career – early influences in the latter field included Webb Pierce and Lefty Frizzell. After an unsuccessful trial with the Pittsburgh Pirates and the appearance of one Elvis Presley in Kilgore, TX, he plumped for music. (Another version of this story has it that Bob turned down an offer from the Pirates having seen Elvis perform.) Whatever, one of the first things he did was record a set of demo tracks under the auspices of Jim Shell, a Texan songwriter. The backing band used was the one belonging to fellow Texan, Mac Curtis.

In 1956, he won a talent competition in Tyler, TX. Reportedly – the source being the Rockabilly Hall Of Fame entry on Bob – he sang Blue Suede Shoes and encored it several times. He won and his prize was an appearance on the Louisiana Hayride. This went so well that he was invited back, which left him needing a band. He recruited local lads, James Burton (who’d already appeared on Dale Hawkins’ Susie-Q), James Kirkland on bass, Butch White on drums and Gene Carr on piano. The ensemble was called The Shadows. The new group recorded several numbers for Abbott Records in California but the tracks didn’t see release until the nineties.

But eventually, after what seemed like some false starts, Luman & the Shadows signed with Imperial in early 1957 and the first session was held in February in Dallas. Singles followed, typically pairing a rocker with something more on teen pop lines. But nothing clicked with the public. In December of that year the Shadows quit their role as support band for Luman and signed up with Ricky Nelson, another Imperial artist. The reasons for the move aren’t documented but one would surmise that there was more of a buzz around Nelson who’d already had plenty of good publicity as a child TV star in The Adventures Of Ozzie And Harriet show. Bob was reportedly devastated and in Spring ’58 switched to Capitol Records, then home of Gene Vincent. Warner Brothers followed in ’59 and it was whilst he was there that he met with the Everly Brothers who suggested he record a song from their regular writers, Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, which they didn’t feel was suitable for them. Bob was feeling low at the time due to lack of record success and was even considering quitting the business and having another go at baseball. The session was held on 22nd January 1960 in Nashville. The songs recorded were Let’s Think About Living – which was actually from Boudleaux Bryant, not the pair – and You’ve Got Everything which would become its flip. There is a rumour – Rockabilly Hall Of Fame – that the Everlys were on rhythm guitar for the Let’s Think About Living session but it’s not corroborated.

The success of the record – #7 in the US Hot 100 and #6 in the UK – didn’t get repeated but Bob kept plugging away and, in 1964, The File on Hickory Records gave him a #24 entry in the US Country Chart. It was to be the start of an initially somewhat hesitant run in the Country Chart which peaked at the start of the seventies with four Top Ten entries. His highest ranking single was Lonely Women Make Good Lovers which made #4 in 1972 (and was co-written by Spooner Oldham).

Although not mentioned in most of the internet biographies but stated in the one from BlackCat Rockabilly Europe, Bob was an alcoholic and that was what eventually killed him in December 1978 at the age of 41 – it appears as ‘pneumonia’ in other biogs. He was a member of the Grand Ole Opry from 1964 till his death. Johnny Cash sang at the funeral.

4. Abbott Records of Southern California was set up by a man called Fabor Robinson. The label’s original rationale was to promote Johnny Horton and Robinson’s focus on his artist was so intense that the first ten releases were from JH. Following Horton joining the team on the Louisiana Hayride in 1952, Robinson picked up other artists and recorded and released records by them. The label’s existence spanned the years 1951 to 1958.

5. In addition to the much more improvised nature of the “wilder” take on Make Up Your Mind, Baby, it’s also faster and higher in key. The thought did cross my mind that a sound engineer could have speeded it up at the request of the producer on a “let’s see what it sounds like if we do this” approach, with the cut then left that way when it was discarded. Although this was purely hypothetical, I did come across a couple of relatively recent, i.e. loaded within the last year, clips on YouTube, put up by record companies rather than individuals. On the clips, both the tone and speed are roughly the same as the released version of the song, leading to the surmise that my theory might have been correct. Explanations for the presence of this version vary: the original non-speeded up tape might still have been present in Imperial’s archives and this was used for the “new” version, or, the “wild” track might have been slowed down in order to approximate to the key that the released version was in. I should add that it’s the faster, higher key cut which appears in the Bob Luman Bear Family Box Set (released in 2006) entitled Let’s Think About Living which does give the faster version some credibility.

6. During 1958 and less so in ’59 and ‘60, Bob was a regular at Town Hall Party which was a country music radio and TV show operating out of L.A. We are lucky in that YouTube has a goodly number of clips of his performances. His take on Shake, Rattle And Roll in October ’58 is fun, and totally OTT. But I’m closing with a slightly more restrained – only slightly – performance from Bob on Oh Lonesome Me, the Don Gibson song which he recorded in 1960. The live take benefits from the presence of another guitar great in Joe Maphis.

Rockabilly Hall of Fame: Bob Luman

Texas Country Music Hall of Fame: Bob Luman

Bob Luman Discography (at 45cat)

Bob Luman at the official James Burton website

Bob Luman biography (Apple Music)

ONE HIT WONDERS ON TOPPERMOST

#1 Jody Reynolds, #2 James Ray, #3 Richie Barrett, #4 Mickey & Sylvia, #5 Scott McKenzie, #6 Blue, #7 Chris Kenner, #8 Dawn Penn, #9 Shep and the Limelites, #10 The Poni-Tails, #11 The La’s, #12 Thomas Wayne, #13 Don Gardner & Dee Dee Ford, #14 Carl Mann, #15 Duncan Browne, #16 Harold Dorman, #17 Ned Miller, #18 Gary Shearston, #19 The Fendermen, #20 Jimmy Radcliffe, #21 Joe Dolce, #22 Sanford Clark, #23 Bob Luman, #24 Jessie Hill, #25 Ernie K-Doe, #26 Irma Thomas, #27 Barbara George, #28 Ray Smith

Dave Stephens is the author of two books on popular music. His first, “RocknRoll”, is described by one reviewer as “probably the most useful single source of information on 50s & 60s music I’ve come across”. Dave followed this up with “London Rocks” in 2016, an analysis of the early years of the London (American) record label in the UK. You can follow him on Twitter @DangerousDaveXX

TopperPost #764

Superb piece. Always loved Billy Lee Riley’s version of “Red Hot’ but Bob’s is as good, if not better. Some other great music here too and good to find out more about the first phase of James Burton’s career.