| Track | Single / Album |

|---|---|

| You Don't Miss Your Water | Stax S-116 |

| Any Other Way | Stax S-128 |

| Crying All By Myself | Stax S-174 |

| Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye | The Soul Of A Bell |

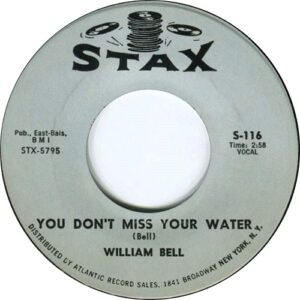

| Private Number | Stax STA-0005 |

| Love-Eye-Tis | Stax STA-0005 |

| I Forgot To Be Your Lover | Stax STA-0015 |

| Left Over Love | Stax STA-0017 |

| Born Under A Bad Sign | Stax STA-0054 |

| I've Got To Go On Without You | Stax STA-0175 |

Contributor: Dave Stephens

“Woefully under-appreciated”, a theme that runs through a goodly number of our Toppermosts, mine certainly not excluded; indeed, I’ve probably written more than most where phrases like “deserved more” are frequently reached for. But is the understandably subjective phrase always as true as we’d like to think it is?

In his review of William Bell’s 2016 album, This Is Where I Live, Robert Christgau commented “… but he was never a star because that voice was never a show stopper”. And, although including two of William’s records in his splendid book, “The Heart Of Rock And Soul: The 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made”, Dave Marsh refers to him as a ‘journeyman’. When I started out on the research for this essay I was hoping to prove both of those statements to be incorrect. Let’s see how I did.

What isn’t in any doubt whatsoever about William Bell is that he has two claims to fame, one mega and the other one slightly less so but still far from insignificant. Let’s take the second one first.

Private Number, released in 1968, was a duet record credited to Judy Clay & William Bell. While Ms Clay had previously worked with Billy Vera in this mode for Atlantic (see footnotes), William hadn’t (or hadn’t on record to be more precise). Stax had released fifteen William Bell singles prior to Private Number of which three had achieved low end Hot 100 positions with his best result in the R&B Chart being #16. It wouldn’t be beyond the bounds of probability that Stax, perhaps getting impatient re William’s chances of seriously cracking the charts, had seized upon an opportunity of a duet with Judy based on her, admittedly limited, success with Billy V, as something that might make things happen. And the fact that Judy was given first billing ahead of William was more likely to have been a tip as to the name the DJ’s and public would see first, rather than some old-fashioned Southern courtesy (though I could be wrong, in which case, apologies).

The song was written by William and Booker T. Jones and the latter handled production duty (albeit not for the first time for William). Stylistically, I guess you’d call the number soul-lite with strings everywhere and mood playful rather than agonised. Plot wise, she’d changed her phone number and gone private so you can guess what he was after and yes – “You can have my private number / (Thank you, baby) / Baby, baby, baby” – he got it. The American audience was somewhat lukewarm about the story – #75 Hot 100 and #17 in the R&B Chart – but over here in the UK we went bananas: #8 in our Top Twenty and he’d only had three records released here beforehand.

I can’t leave Private Number without talking about a few other related tracks. Flip it and you get a number called Love-Eye-Tis which, with a title like that, has to be a novelty dance item and as such, probably disposable. Stick with it though and it’ll start working on you. While the brain appreciates subtle changes in the horn figures each time they appear, the body reacts to the lazy almost sleazy beat and the interaction between the participants. Undoubtedly, Ms Clay brings a lot to the table and she certainly brings out a lot in our Will, He’s feeling it coming on, yes indeedie!

That ease of interaction between the two singers is also noticeable on the flip of a further record from the duo, a speeded-up version of Left Over Love, a song which came from Mable John’s period at Stax and would have originally fallen in the category of soul ballad. Judy leads off this time and a fine job she makes of it. I’m an admirer of the original but the team make a totally new track from the source material. And, contrary to the impression that Steve Cropper had been told to “sound pretty” on some of William’s studio sessions, on this one he’s been given his head to go with the down-and-dirty rotgut stuff competing with the horns who are all over the record like a rash. Arguably, this is a Judy Clay record but even if someone is planning to put a Judy Topper out, I don’t think that matters.

Duets followed with Mavis Staples and then Carla Thomas but the results weren’t quite up to Bell/Clay outings.

A couple of paras back I said that I couldn’t leave Private Number without talking about some other tracks: the last is the follow-up to that record on which the same team worked; that is Bell & Jones, composers, and Jones, producer. I Forgot To Be Your Lover did something rather daring for the 1960s in opening with a quote of the title line from the oldie, Have I Told You Lately That I Love You; these days it would be a sample of course rather than a quote, but same principle. The theme of the song is that he hasn’t given her the attention she deserves as the expanded opening lines make abundantly clear.

Have I told you lately that I love you?

Well, if I didn’t darling, I’m sorry

Did I reach out and hold you in my loving arms

Oh, when you needed me?

Sonically, the coating that the Stax studio give the song is sweet soul of the type we would get very used to from the late sixties/early seventies onwards. Steve Cropper is in pretty sounding mode (though you can be confident it’s him from the little bluesy slides) and there are touches of unison singing provided by producer/arranger Jones which hark back in an understated way to the preceding single. And I love it, which is something I rarely say about sweet soul; even the strings know their place and aren’t overpowering. Below is the marginally longer version (see footnotes for explanation of that comment):

William’s mega claim to fame came with the self-written You Don’t Miss Your Water, his debut on the, then very young, Stax record label. The 45cat writer dates this release as November 1961 and goes on to say “BB (Billboard) Feb 17, 1962 – entered bubbling under chart and, BB May – entered Hot 100, reached no. 95”. And that was it until 1965 when fellow Stax artist Otis Redding gave a (belated) statement of approval by releasing his version of William’s song on the Otis Blue LP in September that year. Otis at the time was riding high in the charts with I’ve Been Loving You Too Long and Respect, and Otis Blue itself would receive a rapturous reception from the critics (and its reputation has, if anything, increased as the years have rolled by). In 1968, the song appeared again, this time on the Byrds’ Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, an album which had a mixed reaction initially but has garnered increasing praise over the years. Certain tracks on the album (which were originally sung by Gram Parsons) were overdubbed prior to release with Roger McGuinn’s voice. I cover the rationale for the overdubbing in my Toppermost on Gram but suffice to say that You Don’t Miss Your Water was one of those. The tracks prior to overdubbing were eventually released in a Byrds box set in 1990. This was the ‘original’ You Don’t Miss Your Water. In the Toppermost I make the comment below on the Parsons/Byrds take on it:

“One of the tracks to reach us in 1990 featured Gram, the Byrds and the Nashville guys covering Memphis soul singer William Bell’s You Don’t Miss Your Water (Till The Well Runs Dry). I say “the Byrds” in terms of who was doing what on this track but in fact the main people you hear are Gram plus Earl P Ball on piano and Jay Dee Maness on pedal steel. And those guys managed to do something that hardly anyone had done convincingly before: conjure up a country version of a black soul number but coming from the white side of the tracks. In 1990 this might not have sounded so unusual but in ’68 it certainly was. Black artists like Solomon Burke and Arthur Alexander had turned country songs into what got termed country soul but from the white side, only the occasional Elvis or Charlie Rich made country soul out of that coming together of black and white music and emotions.”

In the Dave Marsh book I made reference to earlier, he allocates the 290th chart position to the William Bell record and starts off his critique by saying:

“Although Bell’s version of You Don’t Miss Your Water was the first I ever heard, it amazed me that he’d written it. Its cadences suggested something much older – and something much more C&W, too. (Listen to the Byrds’ version on Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, and you’ll see what I mean.)”

That’s more than enough prelude. Here is the track:

Compare and contrast with the Redding version (which a generation of record buyers including myself had grown up with). Otis is Otis, king of that generation of soul singers whose emotions were everywhere and he makes no exception with this song. Its writer takes a different approach and it was one that would characterise much of his output. Dave Marsh closes his critique of the record with the following:

“It’s that very diffidence, the purposeful lack of histrionics, which makes Bell’s You Don’t Miss Your Water so much more extraordinary than any other record of the song. Because the melody is mournful, he sounds sad. But he’s damned if he’s ever going to lose control.”

That says a lot about the record and about William Bell. But there’s more:

* According to Wiki the ‘missing’ aspect of the song was actually related to a feeling of homesickness for his hometown of Memphis, since William was in a New York hotel room when he wrote it, operating as lead singer on tour with the Phineas Newborn Orchestra.

* The record was produced by Chips Moman who was one of the early producers for the label, having started with Stax when they were still Satellite.

* The full title line of the song is “You don’t miss your water till your well runs dry” and it would become the first of a number of solely or jointly written songs which utilised popular sayings or proverbs as titles and narrative material.

* The opening couplet of the song makes use of an early portion of Amazing Grace: “I once was lost, but now am found / Was blind, but now I see” though whether this was deliberate or not isn’t known. And I’m grateful to The New Yorker for unearthing that information.

* The record didn’t see release in the UK. Hence my earlier remark which started “Compare and contrast …”. Indeed, William Bell singles wouldn’t start flowing here until 1967 according to 45cat. I suspect he might have been a casualty of Stax initially being distributed nationally in the US by Atlantic who were represented by London in the UK, then Atlantic switching to direct representation in the UK then Stax doing the same. In addition, William’s military service stint which started after his second single, reduced the flow of singles.

His career at Stax spanned the period November 1961 to July 1974. He wasn’t quite first man in the door, last man out, but he wasn’t far from either. In spite of the lengthy period, his output wasn’t massive – there were no more than one or two singles some years. Five LPs were released though three of those were concertinaed in the period 1971 to 1973. Below are some of the higher points from an output that was very rarely less than enjoyable and often warranted considerably more praise. The tracks are in order of release which gives a feel for the musical changes happening at Stax over the time frame:

Any Other Way (1962 follow-up to You Don’t Miss Your Water): She’s left him but he still has his chin up or that’s the public image – “But when she ask about me, here is what you say / Tell her I wouldn’t have it / Any other way” – with horns utilised in a semi-orchestral manner toning back the more typical punchy riffing (that, contrariwise, does appear on the Chuck Jackson cover of this song).

I’ll Show You (1963): Could have been a minor Redding ballad but without the vocal acrobatics apart from one rather splendid extended “Oh” at approx 1:25 minutes.

Crying All By Myself (1965): Had someone been listening to the Impressions? There’s a choral lead for much of the song with William gradually letting the emotion in the lyrics seep through him, though he holds it together until the fade. Steve Cropper is the co-writer this time.

Share What You Got (1966): Which extends to Share What You Got (But Keep What You Need) as in he’d “give a friend my last dime” but “I won’t share my baby”.

Everybody Loves A Winner (1967): The sayings are starting to appear, this one has the punch line “But when you lose, you lose alone”. Pretty piano from co-writer Booker signifies that soft soul with a side order of melancholia is now in.

One Plus One (1967): That sad piano is retained for this one though William’s not involved with the writing for a change. This time that role is allocated to relative new guys, Isaac Hayes and David Porter, and it was definitely relative since the team had already started providing hits for Sam & Dave – and in case you’re wondering “Did William ever cut any dance tracks” the answer is yes, on this occasion the jumper, Eloise (Hang On In There) was actually on the A-side, a relatively rare occurrence in the Bell/Stax record saga.

Everyday Will Be Like A Holiday (1967): “When my baby comes home” concludes the line, and the lyrics consist of little more than that, making the song another rarity in the Bell/Stax record oeuvre. But would you know that William’s happy? – not really, it’s only the horns that suggest that celebration is in order, and given that the record has become something of a Christmas item, I thought the reader/listener might appreciate the live version from Jools’ Annual Hootenanny, 2015.

A Tribute To A King (1968): In case you were in any doubt – the tribute is to Otis not Martin Luther – it was released prior to the latter’s tragic death, and the lyrics are explicit. We, that is the collective UK public, took a bit of a shine to William for delivering this and gave him a #31 in May ’68 (his first UK chart showing) and then queued up in droves later the same year for Private Number.

Listen, people, listen

I`m gonna sing you a song

About a man who lived good

But didn’t live too long

He was born in Macon, Georgia

A poor boy without a dime

He found his way to Memphis

Singing These Arms Of Mine

Why wasn’t this in the Ten? Let’s just say I was strongly tempted.

Born Under A Bad Sign (1969): Technically, this was a cover but because another Stax artist Albert King needed material, the Bell/Jones song was allocated to him back in ’67 – you’ll know his version and also the one from Cream which appeared on their third studio album, Wheels Of Fire, in 1968 but this one might come as a surprise. Obviously determined to be different, producer Jones has upped the tempo, had William add a homespun spoken intro and funkified the whole thing, in the process creating a valid alternative to the King original (on which, ironically, Booker and the M.G.’s would have appeared in their role as the Stax house band).

That’s not the end of the Born Under A Bad Sign story. As briefly mentioned earlier, an album appeared in 2016 featuring William on the reincarnated Stax label with production by John Leventhal, hubby of Rosanne Cash. A new interpretation of Born Under A Bad Sign was included and once again there was clear intent to move away from the King version. I admit to mixed feelings on this one; it starts well but I could have done without the extra clutter that gets added.

I’ve Got To Go On Without You (1973): Seventies soul and a very good example of the sub-genre, underpinned by a firm basing of funk that doesn’t distract from the song’s message. For once, William wasn’t involved in the writing process but did share production duties with Al Jackson Jr, the drummer for the M.G.’s and frequent Stax producer. He was responsible for the Albert King Born Under A Bad Sign. In addition, by this time, Jackson had spread his wings and been doing some production work at the Hi studio, home of Al Green. It showed.

Stax didn’t deliver an LP from William until 1967 with The Soul Of A Bell but it was worth the wait. The AllMusic reviewer Alex Henderson opened his critique with the following words: “William Bell’s history illustrates just how singles-oriented soul was in the 1960s. Though he’d enjoyed a hit in 1961 with You Don’t Miss Your Water, it wasn’t until 1967 that Stax finally released his first album, the magnificent The Soul Of A Bell”. It was head and shoulders above the ones that followed containing fine versions of Do Right Woman–Do Right Man and, I’ve Been Loving You Too Long (To Stop Now), good singles selections from the preceding years, a couple of decent originals and two other covers both of considerable interest:

Nothing Takes The Place Of You (The Soul Of A Bell): A recent R&B Chart hit (and one which almost cracked the upper half of the Hot 100) for Toussaint McCall – this is the Toussaint original and below is William’s cover. Quite why the Stax team felt there was a need to add another keyboard (vibes) to the mix of piano and organ on the original (which had almost inevitably evoked the sonic mix on You Don’t Miss Your Water) I know not, but in all other respects William delivers a fine version – it’s his kind of song.

Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye (The Soul Of A Bell): The composer of Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye, John D. Loudermilk, was a singer/songwriter whose skills were more recognised in the second of those professions. Although he’s often loosely categorised as a country writer, his songs were recorded by both pop and country artists (see also footnotes). This song is a good example, originally cut by big band singer Don Cherry, with more versions following by broadly pop artists. It didn’t achieve hit status until the release of a version by white vocal group, the Casinos, #6 in the Hot 100 no less in December 1966 (and it wasn’t in doo wop style in spite of what the Wiki writer implies). Subsequent to William’s interpretation, there was a version from recognised country artist Eddy Arnold in 1968 which topped the Country Chart. While lyrically, the song could be said to fit in with country conventions, musically it was more pop inclined with the main sections of the verses utilising, what has become known as the doo wop progression, even though its usage predates that music style by decades.

The gospelly piano introducing the William Bell version tells us immediately that this was soul, and soul with more drama content than sometimes heard from our man – and whether the song was strictly country or not, William and the Stax team had created a piece of music which sat well in the country soul category, alongside his very first disc from six years or so earlier, and had done so with an interpretation of the song’s lyrics more heartfelt than any versions that had preceded it.

Kiss me each morning for a million years

Hold me each evening by your side

Tell me you’ll love me for a million years

Then if it don’t work out

Then if it don’t work out

Then you can tell me goodbye

There are times when I’d put this track on the same pedestal as You Don’t Miss Your Water but maybe that’s just recognition of the fact that I can’t think of William without thinking of that record.

In the beginning

You really loved me

I was too blind

I couldn’t see

But now that you’ve left me

Oh how I cried

You don’t miss your water

‘Til your well runs dry

On 21st June 2013, The White House hosted a concert entitled “In Performance at the White House: Memphis Soul”. William was one of the artists to perform. His song choice was inevitable. This was how it sounded (and that’s musical director Booker T. wearing the bowler).

In “Sweet Soul Music”, Peter Guralnick called William Bell, “perhaps the most underrated of all the major soul singers”. He deserves that accolade for that record alone.

You know what? I’m siding with Peter. Messrs Marsh and Christgau can … (insert your own words).

FOOTNOTES

1. William Bell was born William Yarbrough on 16th July 1939 in Memphis, Tennessee; he took the stage name “Bell” from his grandmother whose maiden name was Belle. Like almost every soul singer you’ve ever heard of, he sang in church as a child but not content with merely singing he also started writing songs from an early age. An example of his prowess can be heard on the 1956 Meteor single, Alone On A Rainy Night credited to the Del Rios with the Bear Cats: the Del Rios were the vocal group within which William was operating and the Bear Cats were the instrumental backing group for Rufus Thomas, named, of course, after Rufus’ hit record. William also found solo work as vocalist for the Phineas Newborn Orchestra.

After the Del Rios had worked with Rufus T as backing singers, they started being used by Satellite Records (which would soon become Stax) in a similar role; in an article on William by uDiscoverMusic.com he recalls being asked in 1960 to provide vocal support on Carla Thomas’ Gee Whiz, her first solo record and one which broke the US Top Ten. In not a lot more than a year, William would have his own debut disc out and much of that story musically is told in the main text.

2. The fact that I took all my selections for the Top Ten from William’s period at Stax doesn’t mean that his record career stopped when the company folded, nor does it imply that there was a serious quality drop in his post Stax records, or that people stopped buying his records after he’d left that label. No, for me there was a gradual decrease in the relevance of his output which started before the Stax collapse and it applies too to other artists who we label as ‘sixties soul’. I’m conscious in saying that I’m confessing to certain personal likes and dislikes but so be it. I would add, in my defence, that William always regarded Stax as home.

That said, a few words on what happened to William next are certainly in order. From 1968 to 1970, he indulged in some extra-curricular activity outside of Stax: this involved the set-up and management of a record label, Peachtree, for a few years. In terms of his own record career, Mercury offered him a contract in 1976, which resulted in a hit with Tryin’ To Love Two on his first outing for the label – it topped the R&B Chart and hit #10 in the Hot 100. His only other hit came in this country in 1986 with Headline News which achieved a #70 rating. We were also rather keen on the album Passion from which that track was selected for single release. The album (and single) were issued via another label that William had set up, Wilbe Records.

Bearing in mind that Peter Guralnick’s “Sweet Soul Music” was originally published in 1986, it’s possible that some of the recognition that Peter said was so lacking, did eventually come William’s way with the operative word being “eventually”. In addition to his inclusion in several important concerts celebrating southern soul music (including the Take Me To The River documentary in 2014) plus the 2016 album I mentioned – on which more below – in 2020 he was made a National Heritage Fellow by the US National Endowment For The Arts and, in their biography of him, the writer stated:

“Bell is the recipient of the Rhythm and Blues Foundation’s R&B Pioneer Award, a BMI Songwriter’s Award, and is a member of the Georgia Music Hall of Fame and Memphis Music Hall of Fame. Although his historic contributions to the world are highlighted and celebrated at the Stax Museum, he continues to write, produce, record, and tour the world.”

3. I make reference in the main text to previous experience that Judy Clay had in duet mode. After solo singles had been released on several labels without success, Jerry Wexler of Atlantic came up with the idea of pairing her on record with white singer, Billy Vera. The resulting record, Storybook Children, achieved positions in both the R&B Chart and the Hot 100. Another single and an album followed, but success was relatively short-lived since television executives at the time were unwilling to allow a two-race pairing to perform together publicly. In an interview with Billy Vera, which is contained within a Stax Records biography of Judy, he states: “To add to the indignity, we went on to see our songs performed on network TV by Sammy Davis Jr and Tina Turner, and by Peter Lawford and Minnie Pearl”. Although she picked up a degree of success from the duet records with William Bell, it didn’t help her solo career and only one record from her, The Greatest Love in 1970, achieved any chart action at all. She made a living as a back-up singer (particularly with Ray Charles) until she left secular music altogether in later years.

4. Have I Told You Lately That I Love You shouldn’t be confused with the later Van Morrison single Have I Told You Lately, written by the man himself, included on the album Avalon Sunset, released as a single in 1989, and on which the title line does continue with the phrase “that I love you”. The Bell/Jones song quotes are from the song written by Scotty Wiseman and included in the film Sing, Neighbor, Sing in 1944 performed by Scotty and his wife Lulu Belle (stage name of course); the duo Lulu Belle and Scotty were known as “The Sweethearts Of Country Music”. The song was subsequently covered by members of country and rock’n’roll royalty including Gene Autry (he had the first official single version), Eddy Arnold, Willie Nelson, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Eddie Cochran, Ricky Nelson (and the ‘y’ was there at the time).

5. I don’t know if I am the only person to have noticed that versions of William’s I Forgot To Be Your Lover vary in length depending on when the fade out is applied. I think, though I can’t be 100% sure, that the version that appeared on William’s 1971 LP, Wow, had the final lines as:

Oh, I’m sorry, I’m sorry, baby

I forgot to be your lover

If you forgive me, I’ll make it up to you

I’m only a man, and I forgot to be

… with the fade occurring over the final couplet. However, the version on the single and on the 1969 LP Bound To Happen fades on the line “I forgot to be your lover” so you don’t hear the final two lines at all. This analysis is backed up for the albums by different timing given for the song by Discogs. Intriguingly, the first line that is effectively dropped is the only one in the entire song that suggests that the pair have had a row about the subject to the extent that she might be threatening to leave. Which raises the question, was this too hard-edged an issue to appear on a soft-sounding single? Might it alienate the target audience? Or am I reading too much into something that might have initially have been an error which was subsequently corrected? Confusingly, there also appears to be an even longer version of the track which runs for roughly a minute more!

6. John D. Loudermilk was born in North Carolina in 1934. He set himself on a music career from an early age and his first recognition as a songwriter came when George Hamilton IV picked up his song, A Rose And A Baby Ruth, after John himself had aired it on local radio. John was still desirous of a singing career back in those days and released several records under the nom-de-plume of John Dee. One of the songs he cut was Sittin’ In The Balcony which came to the ears of Eddie Cochran and, lo and behold, became the first hit for the latter (#18 in the Hot 100). This helped to set John on a writing career. Hits were plentiful through the fifties, sixties and seventies. They included such numbers as Ebony Eyes (The Everly Brothers), Tobacco Road (The Nashville Teens), Abilene (George Hamilton IV) and Break My Mind (numerous).

7. I talked at moderate length about the history of Then You Can Tell Me Goodbye before it came into William’s hands. That was by no means the end of the story; there were plenty more versions still to come. In 1968 and ’69 respectively, Solomon Burke (on the LP I Wish I Knew) and James Brown on his LP Say It Loud, I’m Black And I’m Proud) recorded the song. And artists as varied as Johnny Mathis, David Hasselhoff and Frankie Valli laid down their versions over later years. I also feel it would be discourteous not to mention the version of the song from its author which actually preceded the Bell interpretation.

8. This Is Where I Live, the 2016 album I referred to in the main text, won a Grammy that year for Best Americana album. It’s a strong set and can be looked on as a (belated) equivalent to Solomon Burke’s 2002 CD Don’t Give Up On Me but with the major difference being that William co-wrote all but two of the songs. Below is a clip from its making.

Soul Express interview and discography

Judy Clay (1938-2001) feature at Spectropop.com

William Bell biography (AllMusic)

Dave Stephens is the author of two books on popular music. His first, “RocknRoll”, is described by one reviewer as “probably the most useful single source of information on 50s & 60s music I’ve come across”. Dave followed this up with “London Rocks” in 2016, an analysis of the early years of the London (American) record label in the UK.

Read the Toppermosts of some of the other artists mentioned in this post:

Arthur Alexander, Booker T. & the M.G.’s, James Brown, Solomon Burke, Ray Charles, Al Green, Impressions, Chuck Jackson, Otis Redding

TopperPost #991

Such a superb voice. Bell had a very interesting restrained/ controlled aspect to his singing, which the quote from Dave Marsh picked up on nicely.

Superbly comprehensive Toppermost too as always.

Ditto Andrew’s “Superbly comprehensive Toppermost”. I’d add that in 1968 Taj Mahal did a spine-tingling version of “You Don’t Miss Your Water” on his album, “The Natch’l Blues”. It’s well worth a listen.

Andrew, Steve, thanks for your kind Comments. In terms of quotes, I think I’ll stick with Guralnick but in terms of covers Steve, that one from Taj isn’t bad at all.