| Track | Single |

|---|---|

| There He Goes | IPG 45-1002 (A) |

| That's The Reason Why | IPG 45-1002 (B) |

| Needle In A Haystack | VIP 25007 (A) |

| Should I Tell Them | VIP 25007 (B) |

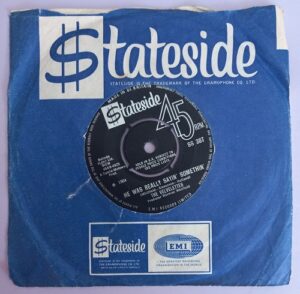

| He Was Really Sayin' Somethin' | VIP 25013 (A) |

| Throw A Farewell Kiss | VIP 25013 (B) |

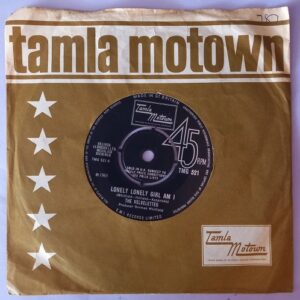

| Lonely Lonely Girl Am I | VIP 25017 (A) |

| I'm The Exception To The Rule | VIP 25017 (B) |

| A Bird In The Hand (Is Worth Two In The Bush) | VIP 25030 (A) |

| Since You've Been Loving Me | VIP 25030 (B) |

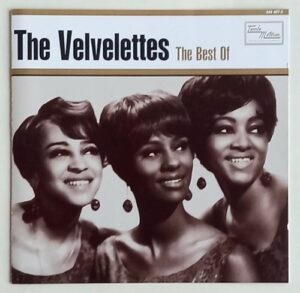

(l-r) Sandra Tilley, Carolyn Gill, Annette McMillan

(Sandra and Annette were recruited to the group in 1967 replacing the Barbee cousins who were raising their families and unable to tour)

Contributor: Steve Devereux

I adore the Velvelettes, the best Motown act most listeners today have never heard of.

At their best, they combine in one group everything that was great about the Supremes, the Marvelettes and Martha & the Vandellas, all at once. Pulled simultaneously in two directions, by the sparkling rush of pure pop and the emotional punch of blues-tinged soul, there’s an alternate universe somewhere out there where the Velvelettes were one of the biggest groups of the Sixties.

That isn’t this universe, of course. The Velvelettes were treated shabbily by Motown: never considered for an LP, their handful of single releases (six of them in total) either nixed by Quality Control or shunted to the lower-profile VIP Records, an imprint of Motown.

But if the group never came close to getting the recognition they deserved, they stayed down to earth, remaining good friends, maintaining a cheerful outlook, not kicking up a fuss – and turning out some brilliant records.

A lot of that has been attributed to their ‘outsider’ status at Motown. Like many of their labelmates, they were young – especially lead singer Carolyn (Cal) Gill, only 15 at the time of this release – but they were also educated, middle-class girls who put academia before showbiz. Cal’s big sister Mildred and her friend Bertha Barbee were both students at WMU in Kalamazoo, having cut a couple of backing tracks for other people’s records as The Barbees; both Mildred and Bertha recruited their younger sisters into the group, Norma Barbee being a full-time student at Flint Junior College.

The original five-strong Velvelettes line-up was rounded out by Cal’s ninth-grade classmate Betty Kelley. Originally calling themselves “Les Jolie Femmes”, they quickly changed their name to the Velvelettes (because they thought their harmonies were “smooth like velvet”) after realising few promoters or DJs could pronounce the French name properly. They were handicapped from the get-go by the Barbee and Gill families insisting their daughters stay in college and finish their degrees (or, in Cal’s case, graduate from high school), rather than heading out on the road. This meant no participation in package tours, no out-of-town engagements or TV spots during term time, and no hanging around Hitsville waiting to catch the crumbs from the top writers’ tables. As a result, they lost ground to their labelmates that could never be made up again; just as Motown was going supernova, the Velvelettes were otherwise engaged.

On to the records …

Having secured a Motown audition through their old contact William “Mickey” Stevenson, the girls impressed Berry Gordy and were promptly signed to a contract, embarking on a number of recording sessions with Stevenson and Norman Whitfield during the spring of 1963.

Quality Control – or “product evaluation meetings”, as they were officially referred to in the corridors of Hitsville – would be the bane of many a Motown artist during the mid- and late-Sixties. Every Friday morning, Hitsville’s brightest minds – not just writers and producers, but sales execs, admin staff, people from throughout the company – would get together to listen to the most promising new recordings that week. Whoever it was in the summer of 1963 who decided these things, Quality Control marked their territory in the expanding label’s organisation by scoring a victory here, denying There He Goes a release.

Embarrassed, Stevenson then seems to have engaged in a bit of face-saving subterfuge; he used his connections to place the rejected record with the little-known Independent Producers Group label who leased the masters from Motown for a year. He was then able to go back to the Velvelettes and point to their record being in stores. It did pick up some radio play but with no Motown promotional money to plug it, the record’s progress stalled before the single had a chance to chart nationally. Supposedly, the girls were completely unaware that the record had been rejected by Motown, and that IPG had picked it up instead, only discovering this some time after the fact.

Opening with a strident burst of slightly off-kilter harmonising before settling into a set routine of midtempo, calypso-inspired rhythm, high, sweet, echoey backing vocals, and a more free-form, soulful lead from Cal Gill with the addition of a plaintively-wailing harmonica courtesy of Little Stevie Wonder way down in the mix.

It’s an excellent calling-card; perhaps it was ever-so-slightly dated by the summer of ’63, but there’s nothing really glaring here to explain Motown’s decision not to release it. It really is quite lovely, and the slightly strident touch that occasionally blights the backing vocals is more than balanced by the smooth, beautiful harmonies the Velvelettes break out elsewhere on the record. Meanwhile, Cal Gill is on sterling form on lead, both handling the difficult vocal line with aplomb – her voice is unbelievably strong for a fifteen-year-old – laying down a marker for the great deliveries she’d turn in over the next five years.

Recorded on the same day as the A-side, There He Goes, and therefore also featuring the talents of Little Stevie on harmonica, this is the heavier and stronger of the two sides of the Velvelettes’ debut single. Opening with a startling, outlandishly-pronounced intro – drums, horns, Stevie’s wailing harmonica, and a strange, oddly-cadenced, almost-chanted group vocal, That’s The Reason Why quickly opens out into a thoroughly enjoyable girl group stomp.

The vocals are excellently confident, and there’s a cheeky smirk in the lyrics which suits lead singer Cal Gill down to the ground. Her delivery is again mature beyond her years, and her sassy, no-nonsense demeanour makes the song completely believable. There’s a great bit right at the very end, barely audible as the song fades down, where Cal explains “So many guys have come around / Trying to take me for a clown”, with a wry, barely-concealed subtext of “but I’m sure you’re not suggesting that sort of thing, are you?” I love it.

Needle In A Haystack was the group’s first official Motown release. The Velvelettes, now down to a three-piece, got a shot at a ‘proper’ Motown 45. It was an opportunity only grudgingly granted, and the group – educated middle-class girls with college commitments, unable to drop everything and move to Detroit at a moment’s notice – didn’t get back to the studio until the summer of 1964, having lost ground to their labelmates that they’d never make up.

The red carpet wasn’t exactly rolled out; despite being assigned to work with the same writers and producers (Mickey Stevenson and Norman Whitfield) who’d been so impressed the first time around, the Velvelettes were shunted to VIP Records, already the neglected member of the Motown label family. If singles on VIP didn’t actually cost any less money, it’s still hard to think of it as anything other than Motown’s budget imprint, especially with that hideous, “no expense spent” yellow label.

So when the Velvelettes turned in what is manifestly the best A-side in VIP’s catalogue to date, and promptly scored the label’s first ever hit on any chart – going Top 50 pop and just missing the Cash Box R&B Top 30 – you’d have expected Motown to take notice, maybe move them to a higher-profile label. But Motown was already well-served for excellent female vocal groups and so the Velvelettes remained in the shadows for the rest of their short time at Hitsville. It wasn’t for want of great records, that’s for sure.

This one still feels a bit like an early effort; all the ingredients are there, everything’s almost ready, but it doesn’t quite gel together. On the one hand, you have Stevenson and Whitfield’s vision for a new Motown Sound – distinct from that being perfected by Holland-Dozier-Holland, tougher and louder, guitar-heavy and with more of a blues influence – which would go on to reap great rewards over the next eighteen months. On the other hand, you have a bunch of standard Brill Building girl group tropes (including a doo-lang doo-lang refrain lifted directly from the Chiffons’ He’s So Fine). The juxtaposition of the various ingredients – Marvelettes-style sass, Chiffons-style clean-cut girl group good times, coruscating sax, muscular bass and heavy drum echo, all great elements in their own right, is a mix that jars every time.

It’s somehow unsatisfying for that reason – Whitfield and Stevenson would shortly be mastering the art of combining sweetness and drive (and unbelievable percussion!) to come up with some great productions, and the Velvelettes would be the best exponents of their art, but for the moment everything about this record seems slightly awkward, slightly forced.

There’s greatness here too, of course – these are the Velvelettes, after all! – not least the fact that it’s absolutely packed full of hooks. Some of them (the drilling intro, the sax break that squeaks as it hits the roof, the crotchet pulse orchestra hits at the end of the chorus) are down to the band, but most of them are the girls’ work, showing off their remarkable skill and timing for interplay.

There’s more than enough here to make it a very good Motown single, and as a calling card it’s hard to top; they were about to get it completely right, and that much is obvious from this record alone, even without knowing what was around the corner. It’s good, but never in a million years is it the one they deserve to be remembered for. A work in progress, a hint of the shape of things to come, that also happens to be very groovy in its own right. That the Velvelettes’ weakest Motown single is still several orders of magnitude better than most artists’ best should tell you all you need to know.

The Velvelettes hadn’t long returned to Hitsville (after more than a year’s absence) when they cut the rush-released A-side, Needle In A Haystack, and so for the flip Motown reached back to the vault and dug out this weird little scribble cut back in February of 1963, back when the girls were a five-piece taking time out from school and college to lay down a few tracks.

This one’s a bit of a mess, if I’m honest. A thin, dated pastiche of the sort of calypso-tinged stuff Mary Wells was using to score hits a year and a half previously, with shrill, jarring backing vocals, it does the group something of a disservice. But it’s the Velvelettes, and nothing they ever did was wholly without merit. This one has plenty of saving graces which take the record above the crowd: the lovely, unexpected chord change which takes us to the chorus, for instance, or the intriguing lyric which sees Cal Gill’s narrator listening to her friends telling her she’s got no chance and no future with the guy she likes, biting her lip as she debates whether or not to tell them that they’re already secretly dating.

The best thing about Should I Tell Them, though, is Cal’s lead vocal. If she’s obviously and noticeably younger than on the A-side, she still gives it her all; like her bandmates’ backing vocals, the performances all bear comparison with their debut. She sounds superb, alternately composed and hurt and she handles difficult parts with aplomb. She’s got power and technique, too; even when the song calls for her to give a long, difficult sustained note, a cry of frustration, at 1:55, she takes it in her stride.

It’s all very impressive, which is more than can be said for the song as a whole – but despite its dated, scruffy nature, there’s the feeling that this has been pulled above its natural level, and it ends up being well worth a listen.

From one extreme to the other, eh?

The Velvelettes, the least heralded and least recognised of Motown’s truly great groups, were different from their labelmates and stablemates in a number of ways. Some of that was their own fault; even after their big break, signing to the label just as things went stratospheric, they refused to compromise on their educational commitments and spent most of their time away from Hitsville, travelling to Detroit for recording dates only when absolutely (contractually!) necessary, unable to tour or to join package shows. In hindsight, this lost time would prove to be gone forever, the gap to their peers which opened up in their absence ultimately unbridgeable.

The Velvelettes never had a US Top 40 hit, never had an album, never really ‘broke’ in the way their talent and repertoire deserved. But it’s no surprise to hear that the music industry is a tough and fickle place, demanding absolute commitment and then laughing in your face even when you provide it. (And the Velvelettes themselves, still friends and still touring together today, don’t seem to bear any grudges about never having become superstars.)

The Velvelettes’ outsider status ended up playing in their favour, or rather in ours. Because they were unknown – and, let’s face it, unwanted – at Motown, where the head of A&R (their one-time advocate Mickey Stevenson) was unable or unwilling to look after them on their rare visits to the studio, they ended up being shunted to a similarly lesser-known writer-producer, a stroppy New York City loudmouth who’d been annoying the top brass with his consistently strongly-worded demands he be allowed to take over the Temptations. (The same Temptations who were currently racking up unprecedented hits under the aegis of Motown vice-president Smokey Robinson, one of Motown owner Berry Gordy’s closest friends. Dream on, mate.)

Norman Whitfield would go on to be one of the all-time greats but, at the time, he was without a project, and Motown probably figured they could shut him up for a bit if they handed him creative control of that misfit out-of-town girl group. But with the Velvelettes he struck gold in a way he couldn’t have imagined. The girls were clever enough to see what he was trying to do and helped him make his half-formed ideas reality on tape. Everyone recognised there was more work to be done after Needle In A Haystack and they set about knuckling down to do it again, and do it better. And that’s how He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’ was made. And it’s brilliant.

This is an immaculately constructed record. There’s perhaps no better possible illustration of the Velvelettes’ unknown greatness than this one, not just because they’re so good here (and they are) but because they make it sound so easy.

However, it’s not just the girls that make this. The rhythm bed, underpinned with a shaken tambourine that’s almost metronomic in its precision and yet at the same time filled with chitlin-circuit menace and guts, has the kind of perfection that only comes with both total genius and a lot of effort. The best horn arrangements yet seen on a Motown single used so very judiciously, from that opening punch in the face to the blaring ship’s horn that keeps the chorus afloat to the closing rollercoaster-on-rails growl to take us out of the song, and weighed out parcel-perfect in a way Holland-Dozier-Holland could only dream of. It’s perfect, and it sounds effortless – but in a bizarre way that also lets you know it didn’t come easy, and now it’s basking in the satisfied glow of a job well done.

Even though the song is good and the Velvelettes’ vocals here are superb, the true greatness of He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’ is that all the pieces are fitted together so beautifully; it’s like a sculpture, or an intricate wood carving slotted together from many separate pieces, but so neatly and so tightly that you can’t see the joins, can’t even feel them if you run your finger over the seams you know must be there. That’s craftsmanship. That’s genius.

There’s nothing I’d change about He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’, not one single second. In this glorious year of amazing records, the very last Motown single of 1964 turns out to be quite possibly the best one yet. And I’m not actually sure it’s even my favourite Velvelettes record. Yeah, they’re that good.

The short-lived partnership between the Velvelettes and Norman Whitfield – both prodigiously talented, both far down the Motown pecking order – produced some very fine records, a run which continues here with another striking experiment.

Throw A Farewell Kiss opens with a sparse, slow three-note guitar sting in a strange time signature, followed by a vast ocean of dead air punctuated only by some distant taps on a woodblock, such that the listener is already thinking “what is this?” after just a few seconds. The record then blossoms into its lovely tune for the verses, Cal and the girls doing their thing in very pretty fashion, but when we reach the chorus and Cal announces she’ll “throw you a … KISS”, everything falls away, and we’re left alone with that weird guitar sting again, just three eerie, stabbing chords, and the girls’ a capella harmonies passing along the torch of the earlier beat in case we forget where we were.

It’s remarkable, not just because it sounds so arresting, bringing a sweet little ballad up into the realms of fascinating records, but because it’s such a brave decision: the fruits of these people not being more famous, and thus being free to take such rewarding risks. And it is rewarding, meaning the song stays in your mind long, long after it’s finished playing.

In order to balance out the forces of the Motown universe, the Velvelettes would have to up the ante too; their new single, therefore, needed to be even better than their previous, magnificent effort. And, somewhat unbelievably, against all odds, it is.

Although the Velvelettes didn’t benefit from being given too many great ideas, the group had shown how incredible they could sound. All it took was a producer who knew what he wanted, and a group who could make it reality. The magic of Lonely Lonely Girl Am I …

I love that title, as though rather than call it I’m A Lonely, Lonely Girl, Whitfield and his co-writers (Edward Holland Jr. and, perhaps unexpectedly, the Temptations’ Eddie Kendricks) decided to favour killer scansion over more fiddly natural speech, gambling – correctly – that after you’ve heard the record even once, it’s done with so much confidence that you don’t even notice the odd title. But anyway –

– the magic of Lonely Lonely Girl Am I is in its immaculate construction; there’s something about a great Motown track, a quality in the air when it all hooks up, where complicated feats of musicianship and singing, and astounding jumps of imagination and melody, just feel absolutely effortless, so that you’re at once in awe of the genius it took to make this work and, simultaneously, carried along for the ride by the apparent ease with which it’s done. If ever you wanted an example of this alchemy in action, look no further than this; the Velvelettes put on the greatest magic show we’ve ever seen.

I like to think of Lonely Lonely Girl Am I as being like a fractal, one of those weird mathematical drawings where no matter how closely you zoom in, all the way down, thousands and thousands of times, you still see the same pattern. This record is made up of a whole load of different elements, put together very carefully in an intricate jigsaw puzzle (and not just any jigsaw; this one is on a par with a 20,000-piece job). Yet never do you get the sense that they’re anything other than parts of a whole, each of them expertly crafted with the finished product in mind. Every person does the best possible job they can do, but it’s all with one goal in mind, a cast of however many all at the peak of their game, directed by a man with a perfectly conceived master plan on a grand scale. This isn’t pop music, it’s architecture.

The dovetailing of all the ingredients that make up this record is a joy, both in its staggering effect and when you get it under the microscope to admire the workmanship. Using a string and bass refrain as half of a call-and-response in the verses, or having the Velvelettes send the chorus soaring up to the sky with a wordless vocal refrain requiring absolutely incredible timing to work, or – at the end – having Cal herself take over the vocal refrain instead? These are choices which feel both inspired and obvious.

Plus, everyone on this knows how good they are. The drums and tambourine are just out of this world. The Velvelettes have never sounded better, their harmonies like multi-coloured ribbons streaming through the sky, wrapping into spirals and loops and complex shapes and then gracefully unravelling like silk on silk. And Cal, who manages to best her incredible lead vocal performance from He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’, is mesmerising as she rolls the words around her mouth, sounding like a veteran singer twice her age as she purrs and growls her way through what might just be the best lead vocal we’ve yet encountered on any Motown record. The lyrics, full of wordplay designed for Cal’s tongue to pick through – “Sly but tender, you deceivingly surrendered your love to me” – exactly fill the allocated space in the track, with not a millimetre’s room for manoeuvre if you miss a cue. Faced with a challenge like that, Cal, of course, doesn’t even blink.

The end result? An absolutely killer tune, that Oh oh oh oh, doo-bee-doo hook guaranteed to stay in your head for weeks, performed in such a way that the bar is now set impossibly high for any female group to even think about covering this. What would be the point? It can’t get any better. The only Motown cover versions of this song are sung by men.

Unsurprisingly, despite receiving little push at the time, this has gone on to be an anthem on the Northern Soul scene, and the Velvelettes themselves speak fondly of it as the closest they ever got to making the record they wanted to make. As well they should: He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’ is a wonderful, wonderful record, well deserving of a place in anyone’s desert island collection – but with all due respect, this is their masterpiece.

There’s literally not one second, not one single second, of this record I’d ever change; it is, as far as I can tell, perfect.

As with the magnificent A-side, Lonely Lonely Girl Am I, this B-side also exists in a slowed-down version by the Temptations. However, unlike the Tempts’ rendition of Lonely Lonely Man Am I – which, although the public wouldn’t hear it for a few years yet, was actually the original version, later sped-up and heavily modified (twice) by Norman Whitfield to eventually become the uptempo pop masterpiece of the A-side – well, here, the Velvelettes’ I’m The Exception To The Rule is the earlier take, and the Temptations’ (beautiful) cover is the thoughtful reinterpretation.

Another difference: in this instance, I prefer the Temptations’ version, which has all but spoiled me for other renditions. While this version’s still nice enough, it’s a jarring experience going from the sleek pop perfection of the A-side and being pitched backwards two years in time, back to when this was originally written.

The strangest thing about it, really, is that Cal Gill doesn’t sound like Cal Gill. On previous Velvelettes 45s, Miss Gill has been among the best vocalists Motown had to offer, her soulful tone and sassy, playful diction marking her out as a natural star, wise beyond her years. Here, though, she sounds like a different person, pushed way up high, far outside her natural comfort zone. For the first time, we’re faced with a Velvelettes record that – fine though it is – doesn’t actually sound like the Velvelettes. What it sounds like, actually, is a record by the Supremes – but the weird, prototype, before-they-were-famous. And, sure enough, that’s exactly what this is, a long-abandoned Supremes number cut (and shelved, and promptly forgotten) in the wake of the Meet The Supremes LP.

I’m The Exception is a nice, but undeniably messy disappointment and it’s the first Velvelettes record where I have to say, hand on heart, the singing isn’t so great. But the song is a great one. We’ll have to wait years to hear it done the way Whitfield might have imagined it in his head, but it’s still a beautiful tune and a great lyric.

Apparently, this song was intended as a follow-up to their previous, stupendous Motown 45, Lonely Lonely Girl Am I. But someone at Motown decided they didn’t like the final mix, cancelling the single and commissioning several new overdubs which were eventually discarded anyway. By the time this sneaked out at the end of 1965, any momentum was lost and the single failed to chart.

But let’s stay on the bright side. A Bird In The Hand (Is Worth Two In The Bush) is yet another fine seven-inch and if it’s not quite the equal of the two world-beating Velvelettes efforts that came before, well, only in Velveletteworld could this be considered any kind of disappointment, because it’s splendid.

In the liner notes to The Complete Motown Singles: Volume 5, lead singer Cal Gill (who provides a lovely series of recollections) singles out the James Jamerson bass and Jack Ashford tambourine on this track for special praise, and she’s absolutely right. To listen to a good Velvelettes record is to be transported, in so many ways. There’s something magical when they hook it all together, something which makes it a lasting regret they didn’t have a longer time in the sun at Motown. Knowing their story was all but finished, on top of the fact that nobody at the time seemed to care, it’s difficult not to start pining for the great late-Sixties Velvelettes songs we never got to hear, the new songs they might have teased out of Norman Whitfield, the amazing records that might have resulted. The pain is eased by the group’s Motown Anthology double CD set, collecting together their considerable unreleased Motown output, which is positively stuffed with quality castoffs – but when you hear something like A Bird In The Hand, which again seems so effortlessly brilliant compared to almost any pop record you care to mention, you can’t help but feel we missed out.

Here, they’re on top form again, their intricate dovetailing harmonies as mesmerising as ever as they swirl and loop around the listener, a three-ring circus of sound with Cal Gill barking like a ringmaster. Apparently, she had a case of laryngitis coming on when her vocals were laid down, accounting for her throatier, raspier lead vocal here in comparison to the smoke and silk of her earlier cuts. Whitfield liked the effect so much he forced her through several takes to get the right amount of breathy worldliness into the sixteen-year-old lead singer for her to convincingly dispense seasoned relationship advice.

It worked; she gives it the full Martha Reeves here, with spectacular results. The chorus is yet another killer stomp of repetitive elements and a blasting 4/4 beat, once again underlining just how good the Velvelettes were at selling this sort of thing, Cal switching off altogether for the other Velvelettes to take up the mantra-like earworm chant – bird in the hand is worth two in the bush now / bird in the hand is worth two in the bush now – and floating over the top with her interjections – remember girls! hold on! – and the high harmonies are just again slotted in exactly right, fitting the rhythm with digital-watch timing – hold on, baby, to what you got! – it’s just a remarkable record.

Not for the first time and not for the last, the Velvelettes come at me with a curveball, showing just how very out of (ahead of, even?) the regular Motown loop they really were. Though this one probably makes more sense now than it did at the time because Since You’ve Been Loving Me isn’t so much soul as it is indie pop.

It’s a startling development, not least because it comes strapped to the back of the rollercoaster assembly-line R&B-pop of A Bird In The Hand (Is Worth Two In The Bush), and it sounds nothing like the Velvelettes at all. What it sounds like, in fact, is a better-sung take on something like The Ace of Cups – slow, thoughtful, padded with great thudding chunks of bass and plaintive guitar riffs. Goodness me, how much I love this. I remember the first time I heard it, it sounded like an artefact out of place, a late-Sixties Californian garage rock ballad feel to it when I was expecting more of the thumping and sweeping and eerie brilliance of the best Velvelettes sides; even now, several hundred plays later, it still exudes a strange feeling, like an interloper.

It’s a weird and unfamiliar experience – but it’s also a riveting one, beautifully written, the unfamiliar writing team of Marv Johnson and Eddie Holland coming up with a Supremes lyric set to an unfamiliar pattern. And here’s Cal Gill, again showing why she was Motown’s least-heralded should-have-been superstar. Absolutely solo for the first part of the record, exposed in the rivulets of dead air that criss-cross the tape between tambourine bashes and vibraphone pling-plongs and that fat-fingered monster bassline, she still ends up turning in an amazing lead vocal. Meanwhile the other Velvelettes are used very sparingly, hardly appearing until the song bursts into full colour.

When that happens, in a full-on, drum-laden choral breakdown a minute and a half into the record, it’s absolutely energising. Up until then, Cal has been in a tussle for superiority with the track, as though she’d been idly voicing some of her private thoughts and just happened to wander near a switched-on microphone; as the track proceeds, she starts to take control, and then suddenly she begins to vault up the stave and ramp up the volume and the drum beat suddenly forces itself to keep pace, switches to a four-to-the-floor stomp, while the rest of the Velvelettes start chanting Keep on loving me, the way that you’re loving me and Cal extemporises over the top in the finest Velvelettes fashion, and just for a moment, the whole thing crystallises and you realise the hairs on your skin have pricked up and this is just special, very very special.

Our contributor Steve Devereux is the founder of the Motown Junkies website, a track-by-track review of every US and UK Motown single, including all subsidiaries – a work-in-progress since 2009.

Needle In A Haystack – ‘Where The Action Is’ – June 1965

Unreleased until the Velvelettes’ Motown Anthology 2CD set in 2005

The Velvelettes final single These Things Will Keep Me Loving You (released on Motown’s Soul label in 1966) has not yet been reviewed on Motown Junkies – but it will be!

Never officially released, the bootleg single was popular on the Northern Soul circuit and can now be found on the Velvelettes’ Motown Anthology

Editorial note: Having covered many of the Motown ‘greats’ on Toppermost, it was evident that one of the gaps that most needed filling was the wonderful Velvelettes. Fortunately, one of their biggest fans is Steve Devereux who has run the fab Motown Junkies site since 2009, and the above post, which you have hopefully just enjoyed reading, is abridged from Steve’s writings on the Velvelettes on his highly recommended website.

Find the full reviews of each of these 10 records by the Velvelettes at the Motown Junkies website: There He Goes, That’s The Reason Why, Needle In A Haystack, Should I Tell Them, He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’, Throw A Farewell Kiss, Lonely Lonely Girl Am I, I’m The Exception To The Rule, A Bird In The Hand, Since You’ve Been Loving Me

The Velvelettes at the Motown Museum website

The Velvelettes biography (AllMusic)

TopperPost #1,032

At some point an ‘alternative’ history of Motown should be done. One that doesn’t focus on The Miracles, The Temptations, Diana Ross, Stevie, Marvin and the ones that have been done to death, but on these groups. This Toppermost shows exactly how it should be done. Magnificent group.

Steve, congratulations – that’s a wonderful, well informed, well written Toppermost on The Velvelettes. (And thank you for introducing a new word to me, ‘nixed’.)

I bought their four Stateside and Tamla Motown releases in the mid-1960’s and, it is true, The Velvelettes were a vastly underrated group.

As with so many ‘if only’ artists, the mind boggles at ‘what might have been’ had The Velvelettes got better promotion and/or enjoyed better luck. Since WWII (when records became really popular) music history is littered with an infinite number of such examples. Motown were not the only guilty party with their recording artists and we must always be grateful for what they did do, not what they did not do – even though that did not benefit The Velvelettes much.

Perhaps, the signs were there from the very beginning…….when they were recommended to audition at Motown by one of Berry Gordy’s relations, the young girls talked one of their fathers into driving 140 miles from Kalamazoo to Detroit in inclement weather to the audition only to find Motown did not do auditions on Saturdays!

There is no doubting that The Velvelettes were a great group and that they were underrated but, personally, I don’t think they top The Marvelettes, who Motown also neglected once The Supremes took off.

Finally, Steve, good luck with your continuing track by track review of every Motown single. Let’s hope that you are not too old before you finish it because that is a mighty task.

Splendido Steve. While you have picked a not unusual theme under the Topper banner; that of taking as your subject an artist(s)who had all the skills/talent/call-it-what-you-like AND made great records but somehow never got the breaks and consequently doesn’t really feature in the annals of popular music, you have produced a document that makes it abundantly clear that these ladies definitely should have made it. You’ve been helped by the fact that the Velvelettes deserve every word of praise that you lavish on them but many thanks for bringing them back to the forefront of my brain (and I did give them a solitary mention, positive of course, in my book, “RocknRoll”),

I should also take the opportunity to thank you for your highly impressive work for the Motown Junkies site. I was very grateful for it in the generation of my Mable John Toppermost last year. I’d add that a key record within Mable’s Motown work (and you know which one) offered an unexpected view of the work of Andre Williams whose Topper will appear soon.