Lloyd Price

| Track | Single |

|---|---|

| Lawdy Miss Clawdy | Specialty 428-45 |

| Mailman Blues | Specialty 428-45 |

| Where You At | Specialty SP 463-45 |

| Walkin' The Track | Specialty SP 494-45 |

| Just Because | KRC GB-587 |

| The Chicken And The Bop | KRC 301-45 |

| Georgianna | KRC 303-45 |

| Such A Mess | KRC 5000 |

| Stagger Lee | ABC-Paramount 45-9972 |

| Where Were You On Our Wedding Day | ABC-Paramount 45-9997 |

DAVE STEPHENS’ NEW ORLEANS SCENES

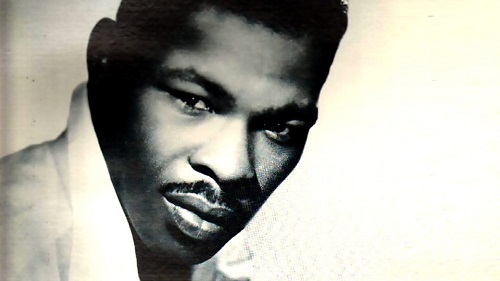

#13 LLOYD PRICE

The night was clear

And the moon was yellow

And the leaves . . . came . . . tumbling

Down

“… four lines that with the perfection of a haiku set the scene with extraordinary tension and grace” (source: Greil Marcus, “Mystery Train” Fifth Revised Edition page 274, on the subject of the opening of Lloyd Price’s Stagger Lee)

Would that I could have conjured up such words but they didn’t occur at the time. I was, however, in seventh heaven. The establishment was telling teen record buyers like me that the short-lived craze for rock and roll was over: Elvis was in the Army, Little Richard had found religion in Australia and Buddy Holly was about to be taken from us in a frozen cornfield near Mason City, Iowa (Stagger Lee was released in January ’59 in the UK acc. to 45cat). If rock was dead it had one hell of a death rattle.

I had no idea who Lloyd Price was, or that he’d been making records since 1952 and had released at least twenty before this absolute cracker appeared. Not only did the whole thing rock like the proverbial clappers containing both a break and a fade from a wailin’ sax man who made that cliché sound as real as hot toasted teacakes with the butter positively oozing out, it had a storyline and hero (or villain?) to add to the John Henrys, the Casey Jones and Tom Dooleys of americana, those mythical beings who were such a significant part of what made the US of A seem so great in the eyes of white teenagers growing up in a largely grey UK which had only seemingly yesterday got rid of rationing. Pause for violins and you’ve all heard this before but that’s not the same as living it.

The Greil Marcus story of Stagger Lee (or Stack O’Lee or Stagolee or various other spellings) starts 12 pages before he gets to Lloyd, though he does give our hero a pat on the back for his interpretation, referring to his “manic enthusiasm” which “many earlier versions lacked” and attempts to answer the question: what was it about this particular barroom brawl ending in a death which caused it to be raised to the level of a myth? In what way did it differ from umpteen other similar differences of opinion? Along the way he asks whether Stack (or Stagger etc.) was black or white, and was Billy (the guy who ended up at the wrong end of Stack’s forty four) black or white? Such questions would assume major importance in the eyes of later interpreters as Jim Crow entered (and departed) the story too. Greil also called it “… a story that black America has never tired of hearing, and never stopped living out, like whites with their Westerns.”

There was also a true-life tale that got attached to the release of Stagger Lee which both Greil and Dave Marsh tell. The initial first verse ran:

I was standing on the corner

When I heard my bulldog bark

He was barkin’ at the two men who were gamblin’

In the dark

So in addition to murder there was gambling involved. Shock, horror! Dick Clark, the powerful presenter of American Bandstand, chose to act as protector of the nation’s innocent youth by insisting that Price change the lyrics if he was to appear on the show. He did and the label recut and rereleased the record, making the original disc one of the earliest to be banned. Strangely, it’s that original we hear these days.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the US and …

… roughly during that same timeframe (and certainly while EP was still in the Army), RCA issued two LPs of his work containing what was effectively filler, i.e. tracks cut earlier or obtained from Sun via the historic deal with Sam Phillips – the ‘filling’ was aimed at getting Presley fans to part with money while their idol wasn’t making regular visits to the recording studio. Both were unusual in that one had no title on the sleeve (but on the record the forename ‘Elvis’ appeared) and the other, A Date With Elvis, didn’t contain a track list on the sleeve. I still have both, one reinforced with yellowing sellotape, and to this day would maintain they’re two of the greatest Presley albums ever, even if they were effectively little more than compilations. Pretty early on in my discoveries of the goodies present on the vinyl, I picked up on two particular tracks, Money Honey and Lawdy, Miss Clawdy (both on Elvis). Given the lack of internet at that time, it took me a year or two to discover that the first came from the Clyde McPhatter version of the Drifters and the second from Lloyd Price, yes the same Lloyd Price of course.

Dave Marsh (writing in “The Heart Of Rock And Soul: The 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made”) says in reference to this single, “More than anything Fats did in this period, “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” set the pattern for the rock and roll years in New Orleans especially through Earl Palmer’s loping, midtempo shuffle beats with their busy ride cymbal …” and he has a point. While Domino might have had as good a claim as anyone to have started it all with The Fat Man way back in 1949, there’s a rougher edge to the Price record and it runs right through, from the vocal to the accompaniment – and yes, that is Fats on the piano – to the lyrics. It’s blues, yes, but blues with a whopping great beat. Just check out that unison booming sound on the turnaround which gives Lloyd the platform for the following verse:

Well lawdy, lawdy, lawdy Miss Clawdy

Girl you sure look good to me

But please don’t excite me baby

I know it can’t be me

Lawdy Miss Clawdy and Stagger Lee were, by a country mile, the two greatest records Price ever made, indeed they stand out as highlights during their respective years of release. There’s an argument that I sometimes put to myself: did Lloyd find an extra gear or something of that kind for these two? He was certainly a major self-promoter (which skill he harnessed with business acumen to become something of an entrepreneur in later life) but I’m talking here more about bringing a greater level of intensity to his contribution to a session. There is a story that appears in numerous places about the making of the debut disc. Art Rupe, founder of L.A. based Specialty Records who was in New Orleans scouting for talent, listened to Lloyd but was going to give up on him when the young gent turned on the crying and pleading show, singing an emotion packed Lawdy Miss Clawdy to Rupe, and that did the trick. And as to Stagger Lee, there’s also a strong suggestion that Lloyd was so determined to make it at ABC Paramount after getting a sniff of semi-success at his own label KRC a couple of years or so earlier, that he and long-time friend and collaborator, Harold Logan, worked up the arrangement themselves using elements of ‘traditional’ New Orleans styling plus newer components such as the strongly featured background singers.

The B-side to “Miss Clawdy”, Mailman Blues, which was cut at the same session with the fat man at the keys, also appeared on his first LP only in a rerecorded version since that LP was on ABC Paramount. I like both versions; the first is more organic with the impression given that the musicians are feeling their way into the number, but by the end the horn riff is driving the whole thing along nicely. On the second, Lloyd opens with a scream and with the obvious intent to start at the top and stay there with a hard driving beat that doesn’t let up. Both drums and horns are to the fore but the pianist still evokes memories of Fats. I’ve stuck with the first; I’m also conscious that it’s tempting to label the early take ‘rhythm and blues’ and the second, ‘rock and roll’ but that would be glib and an over-simplification.

It should have been plain sailing after that. After all, the records from his erstwhile pianist seemed to have a limpet like attraction for the R&B Chart and, as time rolled on, its pop equivalent. But after a tiny handful of top tenners in the R&B Chart, the hits dried up for Lloyd. His records weren’t bad but it was difficult to match “Miss Clawdy”; they didn’t have the wider charms that Fats and Dave Bartholomew increasingly built into the Domino output.

Lloyd tried the clone formula. Restless Heart (which could be found on the B-side of the “Clawdy” follow-up) wasn’t a lot more than a revisit to the hit. He tried out-and-out jump blues: Where You At was an excellent example of the genre with brash snorting horns and back-up male chanters echoing the exultant mood of the front man. It rivalled discs from the established masters like Joe Turner and Roy Brown. There were also ventures into slow pleading blues in Lloyd’s repertoire; the 1955 coupling of Lord Lord Amen and the even slower, Trying To Find Somebody To Love, was a notable double dose with both productions being of the type we’d now call soul blues.

I’m rather partial to a cut from 1954, Walkin’ The Track, an urgent but lazy medium tempo blues which could only have come from New Orleans. Two riffs compete for our attention with the horns switching between them, and Lloyd doing the whistle thing indicating that that darn train is leaving the station:

Come 1954, and Lloyd, like other men of his age, was drafted into the US Army which meant Korea. The time wasn’t wasted according to this account:

“Because of his musical background, though, he was placed into the Special Services (entertainment) branch, where he was put in charge of a large dance band that played “swing” music to entertain the troops. It was here that Price got the idea for what was to become his trademark style: combining a lush, full orchestra with the grittier, rawer tempos and vocals of R&B.”

How much truth there was in that I don’t know since such a vision, if there was one, didn’t get realised until he signed with ABC Paramount in late 1958. The music world had certainly changed, though, while he was off with Uncle Sam. Little Richard and a new thing called rock and roll were ruling the roost both at Specialty and points beyond. Lloyd made three more singles for the label with a couple of those sides, Country Boy Rock and Rock ‘N’ Roll Dance aimed at the new audience but, in my eyes, falling short. Much better for me was I’m Glad, Glad, a jumper, more in line with his usual style but at twice the usual pace.

In September ’56 he left Specialty after a disagreement with Art Rupe. It didn’t take him long to find his feet again. According to 45cat, his first single for a record label called Kent Record Company (or KRC as shortened on disc labels) which he had set up with Harold Logan and another gent called Bill Boskent, was released in January 1957. Let’s just pause there for a moment. In 1956/57, record labels owned by blacks weren’t exactly thick on the ground; record labels owned by black R&B singers were even more of a rarified species.

That single was called Just Because and it’s one that, with the benefit of hindsight, can be seen to have spawned a whole series of records with strong melodical resemblance to each other, which generally get labelled as ‘swamp pop’, a form of music which became popular in SW Louisiana and SE Texas in the late fifties and early sixties. But that’s looking forward from Just Because. What about backward? Look up SecondHandSongs with the song title and you’ll find:

“The music used by Lloyd Price for “Just Because” is almost identical to that used in “A Little Word” recorded by fellow New Orleans based performers, Shirley and Lee. Only the musical bridge is different.”

This is Shirley Goodman leading off the Shirley & Lee single (which was released in January 1956). If you use SecondHandSongs again to dig back further into the origins of A Little Word, ostensibly written by Leonard Lee, you’ll find:

“Adopted from: Caro Nome written by Giuseppe Verdi, Francesco Maria Piave”

So there you have it. Just Because (and a not insignificant tranche of swamp pop) was derived from the aria from Rigoletto sung by Gilda, Rigoletto’s daughter, in Act I, Scene II. This is Maria Callas singing Caro Nome.

But none of that can detract from the fact that Lloyd Price’s Just Because was a mighty fine record in its own right. While there were pleaders and slow blues cut while he was at Specialty – Trying To Find Somebody To Love and Breaking My Heart are good examples – there was nothing that escalated the drama to semi-operatic level the way this did. The arrangement (presumably from himself since no one is credited on 45cat), from the solitary tripletting piano over which Lloyd utters the first high notes before descending with the horns emphasising the phrasing via long sustained big and beefy single notes, to the minimalist middle eight which ratchets up the tension.

Just because you left and said goodbye

Do you think that I will sit and cry

Even if my heart should tell me so

Darling I would rather let you go

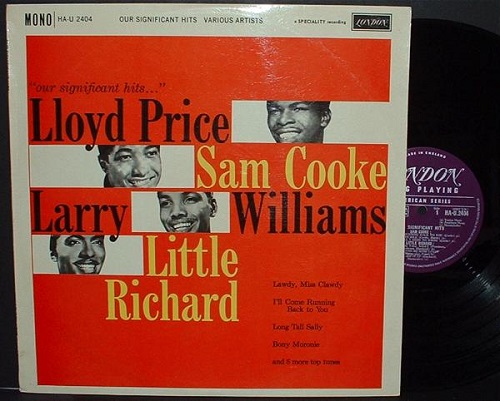

Just Because started selling well locally to the extent that KRC needed help with the distribution so a deal was struck with ABC Paramount. The record hit #3 in the R&B Chart and #29 in the Hot 100. A cover was cut by Lloyd’s cousin Larry Williams which reached #11 in the R&B Chart but did zilch in the Pop Chart (and if you’ve read the Williams Toppermost you’ll be aware of some of the Caro Nome story and you’ll also find a possible explanation of why Lloyd left Specialty).

Lloyd played his clone trick again on the follow-up Lonely Chair which was almost as close as you could get to Just Because. Not too many of the record buying public were impressed judging by the fact that the disc only reached a lowly #88 position in the Hot 100. Mind you if a deejay had thought to flip the record and plug the flip, things might have been different. Cashbox gave the A-side its Award o’ the Week and said about the flip:

The Chicken And The Bop is a quick beat rock that Price shouts out for a change of pace. It is the story of a ball and the two dances, “the chicken hop” and “the bop”. Good jump wax that the kids will cotton to, but for the action it should be “Lonely Chair”. (Source: an upload in 45cat by commenter Mickeyrat.)

Whatever one thinks about his cloning and borrowing – and there was more to come – the records that Lloyd cut at KRC did seem to have a freshness about them, so maybe there was something akin to that vision thing going on that I mentioned earlier in reference to his army stint. Georgianna has a bit of both. From the introduction it’s immediately clear that the record is a blatant lift from Smiley Lewis’ Tee Na Na. Out of loyalty to Smiley, I hesitated before including this one in the ten but its sheer infectiveness won out in the end – play loud!

And for invention, could you beat Such A Mess? A near single chord affair with lyrics which, when I can make them out, do little more than run through the attributes of a lady and her apparel (though Lloyd sounds like he’s having a ball). This should have at least become a cult classic but judging by the lowish number of views on YT this didn’t happen. Shame, maybe the track was perhaps a tad on the revolutionary side for 1959.

As the reader has probably already guessed, or knew, Lloyd hit big with Stagger Lee, his debut disc for ABC Paramount: number one in the US Hot 100 and seven in the UK. This feat allows me to pose the rather rhetorical question: given that this was the third time in a row that Mr Price had been successful with a debut disc for a record company, could he manage to make this success last? The answer of course is yes, at least for a couple of years; while it tailed off in the second half of 1960, it was still a pretty good run, made even better for Lloyd by the fact that he was invariably listed as co-composer of the songs in this timeframe (usually along with Harold Logan). While he didn’t make numero uno again, he came close with Personality hitting the number two spot in the US (but only number nine on this side of the pond). Whilst for this listener it’s a record that’s distinctly inferior to Stagger Lee, these days it gets more radio plays so it’s probably how Lloyd is ‘remembered’. And you do need to see this live/lip synched clip if only to wonder at the seriously under deployed horn section – the trumpets get a few blasts but the sax players (and there are a lot of them) don’t get to do anything other than jiggle around to the music.

It was with records like Personality and Where Were You On Our Wedding Day – see below – that Lloyd established a pattern that caught and held record buyers’ attention for a couple of years or so: the good time atmosphere, frequent usage of big brassy orchestration (conjured up by Don Costa in the early days at ABC) plus heavy utilisation of the Ray Charles Singers who seemed to be everywhere on the records (and for anyone who doesn’t know, these good folk were nothing to do with the Ray Charles you might be thinking of) in a kind of call and response manner, all had their roots in the Crescent City. But the extremely simple melody lines and lyrics which added almost a nursery rhyme atmosphere came, one assumes, from Lloyd himself. Calling these records pop or a dumbing down of Lloyd’s original New Orleans sound is an easy way to describe them but doesn’t really do the discs justice. Certainly, there was no one else in pop who sounded like him either before or after.

And I don’t entirely dislike this series of singles so felt that there should be one number from this period in the ten for it to be representative. Personality seemed just too obvious so I’ve gone instead for Where Were You On Our Wedding Day which does have more touches of NOLA about it than later tracks, perhaps because it was the record that followed Stagger Lee. The fast ska sound does manage to evoke a little fantasy of steamy bars on Rampart St.

After record success dried up, Lloyd moved more into music management, founding a couple of record labels, Double L – the springboard for Wilson Pickett’s solo career and on which he recorded If You Need Me – and Turntable, and opening a club in New York City. While he never stopped performing (and recording) he also got involved in a mind-boggling array of extra-curricular activities. The three sentences below which I’ve lifted bodily from the Wikipedia article on Lloyd give a flavour of these:

“During the 1970s Price helped the boxing promoter Don King promote fights, including Muhammed Ali’s “Rumble in the Jungle”. He later became a builder, erecting 42 town houses in the Bronx.”

“Price manages Icon Food Brands, which makes a line of Southern-style foods, including Lawdy Miss Clawdy food products, ranging from canned greens to sweet potato cookies, and a line of Lloyd Price foods, such as Lloyd Price’s Soulful ‘n’ Smooth Grits and Lloyd Price’s Energy-2-Eat Bar, plus Lawdy Miss Clawdy clothing and collectibles.”

“In 2011, Price released his autobiography, The True King of the Fifties: The Lloyd Price Story, and worked on a Broadway musical, Lawdy Miss Clawdy, with a team that included the producer Phil Ramone. The musical details how rock and roll evolved from the New Orleans music scene of the early 1950s.”

I scratched my head a bit over the question of how to finish this piece on Lloyd Price. He wasn’t the greatest vocalist in the history of R&B and rock and roll though his singing was always adequate and sometimes more. He wasn’t the greatest songwriter although no one can deny that his name is at least one of the ones in the composer spot of a very tiny handful of some truly great records. Eventually I stumbled over the quote below from writer Jack Newfield which appeared in a 2004 New York Sun review of a Rolling Stone article which declared that Elvis Presley had invented rock ‘n’ roll.

“No one person started rock ‘n’ roll. It was a black and white alloy of Fats Domino, Lloyd Price, Ike Turner, Hank Williams, Joe Turner, Louis Jordan, Ray Charles, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Buddy Holly – and Elvis Presley.”

FOOTNOTES

1. Lloyd Price was born on 9th March 1933 in Kenner, approx 12 miles west of New Orleans but also on the banks of the Mississippi (and a township which had already seen the birth of Chris Kenner). According to Wiki, Lloyd had formal training on trumpet and piano in his youth and also sang in his church’s choir (something he’s subsequently denied). With his younger brother Leo, he formed a band called the Blue Boys while both were in their teens and, in 1951, wrote his first song, Lawdy Miss Clawdy. According to BlackCat Rockabilly Europe it was Dave Bartholomew who heard the song and arranged for the audition with Art Rupe of Specialty Records; Dave, at the time, wasn’t working with Imperial, the other L.A. based label which specialised in recording artists from New Orleans. It was Dave Bartholomew’s band which accompanied Lloyd on that first session with Fats on the piano stool.

2. Lloyd’s brother Leo later co-wrote two songs for Little Richard: Send Me Some Lovin’ and Can’t Believe You Wanna Leave, the former with John Marascalco and the latter with Richard himself. Wiki states that Leo also claimed to have written Sam Cooke’s You Send Me and unsuccessfully sued for the publishing rights.

3. The 12 plus pages on Stagger Lee that I refer to in the main text are the ones that are present in the “Notes And Biographies” section of “Mystery Train”. I neglected to mention the chapter headed “Sly Stone: The Myth Of Stagger Lee” which Marcus starts by devoting a page long quotation from Bobby Seale, the Black Panther Party co-founder, wherein Seale explains why he gave his son the name “Staggerlee” amongst others. He (Marcus) then spends the best part of three pages talking about the myth.

There’s actually a whole book devoted to this myth with the title “Stagolee Shot Billy”, written by Cecil Brown which started life as a PhD dissertation in 1993. Rather than forking out for that there is also an online article entitled “A Christmas Killing: Stagger Lee” written by Paul Slade. It isn’t as large as the Brown book but is extremely comprehensive covering facts, stories, music and analysis (and an Appendix giving theories as to why ladies coming to Stag’s funeral should come dressed in red!). I’m indebted to Cal Taylor for pointing me in the direction of this article. It clearly identifies the shooting as being between two blacks, Lee Sheldon and Billy Lyons, in a bar in St. Louis. Cal also gave me a link to a contemporaneous press cutting which illustrates the rapidity with which mythology grew around the shooting. It’s headed “RESULT OF A FEUD: Christmas Killing Said to Have ”The Four Hundred’s” Vengeance” and the first two paragraphs read:

“If information imparted to Coroner Wait Friday is true, the shooting of William Lyons by Lee Sheldon alias “Stack Lee” Christmas was deliberately planned and was the result of an old feud between two negro factions.

“Lyons was a relative of Henry Bridgewater who keeps a saloon at Eleventh and Lucas Avenue, and a stepbrother of Charles Brown who killed Charles Wilson in Bridgewater’s resort about five years ago. Brown was acquitted. Wilson belonged to a club known as the “Four Hundred” which hangs out at Bill Curtis’ saloon, Eleventh and Morgan Streets. Lee Sheldon is president of the club.”

4. In terms of comparison between the Price and the Presley versions of Lawdy Miss Clawdy, this is what I wrote in “RocknRoll” …

“Elvis’ version is far better known and it’s excellent. However, Elvis and the guys at RCA had a splendid master from which to draw and they were careful to retain much of Lloyd’s original. For preference I’ll go with Elvis but it’s a pretty close thing.”

… and bear in mind that I heard (and loved) the Presley take first.

5. Specialty Records achieved a number of successes but for many it’ll mainly be remembered for being the label that, three years or so after Art Rupe met Lloyd Price, would wave the magic wand over Little Richard, turning him into a near overnight star

6. The musical trail which led to the Lloyd Price version of Stagger Lee is tenuous at best, with records showing a wide variety of lyrical content and tunes that don’t often bear much relation to each other, even if the basing is some form or variant of twelve bar blues. There’s also at least one red herring in the shape of Ma Rainey’s Stack O’Lee Blues (released in 1925) which owes more to Frankie and Albert/Johnny (“he was my man but he done me wrong”). However there’s no doubt whatsoever about the version that directly preceded the Price cut: it was the one released as Stack-A-Lee (in two parts) by fellow New Orleans resident, the pianist and singer, Archibald in 1950. The record hit the #10 position in the US R&B Chart in June that year. There’s no way Price could not have heard it and his version sticks very closely to Archibald’s Part 1 apart from the addition of that opening line. In the words of Cecil Brown:

“Cox (surname sometimes associated with Archibald – DS, and see below) accused Price of ripping him off, and in fact both the lyrics and the music are very similar. But Price’s white audience made his rendition a rock-and-roll hit”.

And in reference to that Archibald/Cox thing, this is Joop Visser from the sleeve notes to the box set Getting’ Funky: The Birth Of New Orleans R&B:

“Archibald was one of the last in the long list of New Orleans barrelhouse piano players. He was born Leon T. Gross on September 14. 1912 just off Plum and Hilary in the city of New Orleans.”

He took the name “Archie Boy” or “Archibald” while playing. Quite where the “Cox” came from I’m less sure but you sometimes see it appended as a surname.

7. In the interview with Lloyd by James A. Cosby for PopMatters dated 2nd Feb 2016, Lloyd reveals where he got the title for Lawdy Miss Clawdy:

“And when I heard [the phrase] “Lawdy Miss Clawdy!” maybe a year before I recorded it, I heard a black disc jockey, the first black voice that I was ever able to recognize on the radio. His name was Okie Dokie Smith and he came on and said, “Lawdy Miss Clawdy! Eat your mother’s homemade pies and drink Maxwell House coffee!” There was no way I could mistake him for a white man. So when he said “Lawdy Miss Clawdy!”, the only time we ever said anything about the Lord in our house was on Sundays and he would say it all through the week. But somehow that phrase just stuck with me.”

8. The saga of songs featuring Stagger Lee didn’t stop with Lloyd Price. Of the ones that stuck with the recognisable melody line, the rendition from Dr. John which appeared on the 1972 album Dr. John’s Gumbo is probably the most well-known. There are claims that the good doctor was capable of singing the song for over an hour without repeating himself. Of those artists who chose the Stagger Lee figure as merely a starting point, it’s Nick Cave and the Clash who tend to get the mentions in articles. This is Cave live (but not broadcast) on Austin City Limits – watch out for the appearance of Warren Ellis on violin. The Clash story is a little more complex. Their ‘version’ (which appears on London Calling) features a brief snatch of Stagger Lee prior to them launching into another song, Wrong ‘Em Boyo. The last named number originally came from Jamaican band, the Rulers who also included the snippet from Stagger Lee. The Clash, however, did contribute extra lyrics. It’s worth adding that in “A Christmas Killing”, Paul Slade states that the Rulers composition was an answer song to Prince Buster’s 1966 record, Stack O’Lee.

9. Lloyd might never have had anyone quite as illustrious as Fats Domino on piano on discs other than those cut at his first session, but he did pick up another fine keyboard rattler in the KRC period who stayed with him for the first few discs at ABC (including Stagger Lee). That man was “Big” John Patton (who wasn’t big but picked up the name from the 1961 country song Big Bad John from Jimmy Dean).

Patton was born in Kansas City in 1935. I’ll let Pete Fallico writing in Wayback Machine on 17th January 2016, pick up the story:

“One night in Washington D.C., he ran into Lloyd Price who was appearing at the Howard Theater and just happened to have been looking for a new piano player. John’s audition for Lloyd consisted of playing the introduction to ‘Lawdy, Miss Clawdy’ before he was given the job. This R&B combo soon expanded as did John’s responsibilities and awareness. “I learned everything with Lloyd. I was his ‘strawboss’ and the leader and he dumped all this on me and that was an experience that I got a chance to deal with.””

That meeting took place in 1954. John was 19 at the time. After he left Lloyd, perfectly amicably we’re told, he switched to Hammond organ. In the early sixties he started working with the Blue Note label, initially as a sideman for the likes of Lou Donaldson and Grant Green but launching his own career with the album Along Came John in 1963. It was to be the first of many. In terms of style, the Patton approach was “somewhere between Jimmy Smith and Booker T. Jones” (source: The Guardian obituary 29th March 2002). Georgie Fame was a fan of Big John back in the day and tracks like The Silver Meter (written by drummer Ben Dixon who was also in the Lloyd Price band) was a record which, for me, typified the London mod scene in 1963/64.

10. During the course of putting this Toppermost together and mailing it to the editor, the Blackcat Rockabilly Europe site (which is referred to in the text) was taken down. After a couple of days during which the editor and I modified this post appropriately and commenced the process of making retrospective changes to others, we became aware that the biographies that had been on the Blackcat site had been relocated to a new site, TIMS – This Is My Story. Since then I have been in contact with Dik de Heer and can report that the new housing for his work is intended to be permanent. We will be reflecting the switch in earlier Toppermosts which make reference to the now defunct Blackcat Rockabilly Europe site.

11. I mentioned swamp pop in relation to Lloyd’s Just Because. Anyone who wants to wander further into the Louisiana bayous need go no further than the Toppermost devoted to Freddy Fender (And Even More Of That Weird And Wonderful Swamp Pop Music) wherein I plopped Just Because into the Ten.

12. A few covers have got a mention in this essay; there were plenty more. The reason why Lloyd didn’t achieve a higher chart rating over here with Personality might be due to the UK version coming very promptly from Anthony Newley though my vote on this number would probably go to the easy country swing of Jerry Lee Lewis on the first of his Elektra LPs. Just Because picked up a goodly handful of covers from the very swamp poppy Joe Barry (with the Domino creole lilt) to the rather less swamp poppy John Lennon (digging into his memory banks in Rock ‘n’ Roll of course). Of the more obscure numbers, Doug Sahm gave the world a fine jumping rendition of The Chicken And The Bop on 1989’s Juke Box Music. Of the less obscure numbers, the best version I found of Lawdy Miss Clawdy (other than Lloyd & El) came from Solomon Burke on an obscure Atlantic flip in ’66. But I was not at all displeased to stumble over a 1994 live duet of Lloyd singing the number with assistance, vocally and pianistically, from the recently deceased King (and Queen) of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Little Richard. Just look at those eyes!

SHOT IN CURTIS’S PLACE

“William Lyons, 25, coloured, a levee hand, living at 1410 Morgan Street, was shot in the abdomen yesterday evening at 10 o’clock in the saloon of Bill Curtis, at Eleventh and Morgan streets, by Lee Sheldon, also coloured.

“Both parties, it seems, had been drinking, and were feeling in exuberant spirits. Lyons and Sheldon were friends and were talking together. The discussion drifted to politics, and an argument was started, the conclusion of which was that Lyons snatched Sheldon’s hat from his head.

“The latter indignantly demanded its return. Lyons refused, and Sheldon drew his revolver and shot Lyons in the abdomen […] When his victim fell to the floor, Sheldon took his hat from the hand of the wounded man and coolly walked away.” (St Louis Globe-Democrat, 26th December 1895 – source: the Paul Slade piece)

“Police officer, how can it be?

You can ‘rest everybody but cruel Stack O’ Lee

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O’ Lee

“Billy de Lyon told Stack O’ Lee, “Please don’t take my life

I got two little babies, and a darlin’ lovin’ wife”

That bad man, oh, cruel Stack O’ Lee

“”What I care about you little babies, your darlin’ lovin’ wife?

You done stole my Stetson hat, I’m bound to take your life”

That bad man, cruel Stack O’ Lee”

(Source: First three verses to the lyrics to the 1928 Stack O’ Lee from Mississippi John Hurt)

“Staggerlee shot Billy … Billy the Lion. Staggerlee had a sawed-off shotgun and a Model A Ford and he owed money on that as well; his woman kicked him out in the cold ‘cause she said his love was growin’ old. Staggerlee took a walk down Rampart Street, down where all them baaad son-of-a-guns meet. By the Bucket o’ Bluuuuuud.” (Source: the 1970 jailhouse interview with Bobby Seale as transcribed in Greil Marcus’ “Mystery Train”)

“GO STAGGER LEE! GO STAGGER LEE”

(Source: the backing vocals from the Lloyd Price Stagger Lee record)

“Stagger Lee” was a “B” side. One take; I spent no time with it! Don Costa laughed, because I put it on the back of a song called “You Need Love.” That was supposed to be the hit: strings, nice voices (singing “You need Loooooove”). He said, “You’re gonna put this on the back of ‘You Need Love’?” and I said “Yes. (Source: Interview with Lloyd by George W. Harris of Jazz Weekly dated 1st December 2019)

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame: Lloyd Price

Lloyd Price discography at 45cat

Lloyd Price biography (AllMusic)

Dave Stephens’ New Orleans scenes

#1 Fats Domino, #2 Chris Kenner, #3 Jessie Hill, #4 Barbara Lynn, #5 Benny Spellman, #6 Ernie K-Doe, #7 Irma Thomas, #8 Barbara George, #9 Earl King, #10 Smiley Lewis, #11 Professor Longhair, #12 Shirley & Lee, #13 Lloyd Price, #14 Dr. John, #15 Huey “Piano” Smith, #16 Roy Brown, #17 Johnny Adams, #18 Eddie Bo, #19 Guitar Slim, #20 Clarence “Frogman” Henry, #21 Bobby Mitchell

Dave Stephens is the author of two books on popular music. His first, “RocknRoll”, is described by one reviewer as “probably the most useful single source of information on 50s & 60s music I’ve come across”. Dave followed this up with “London Rocks” in 2016, an analysis of the early years of the London (American) record label in the UK. You can follow him on Twitter @DangerousDaveXX

TopperPost #871

Yet another brilliant Toppermost. And what a great record ‘Lawdy’ is… Wasn’t expecting to see Callas (who was one of my dad’s favourite singers) or Verdi (who was one of his favourite composers) mentioned here either.

I wanted a singer to demonstrate the resemblance between the Rigoletto aria and Just Because and who better than Callas? And I have to confess that I hadn’t come across the full linkage between that aria, Leonard Lee’s song and Lloyd’s ditty until doing the research for this Topper. It was also pleasing (but totally unplanned) that I’d managed to shine a little bit of light on Leonard’s song in the Shirley & Lee Topper in the not very distant past.

I’d add that I wholeheartedly agree with your comment re “Lawdy”. Elvis was an absolute connoisseur of early fifties R&B.

Another fabulous Toppermost by Dave – well written, thoroughly researched and entertaining. There have been countless views aired as to what was the first rock’n’roll record and I am not suggesting ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ by Lloyd Price be considered in that impossible-to-get-a-definitive-answer debate. However, recorded in 1952, I would champion it as being one of the most highly influential rock’n’roll records ever made. Also, I would like to praise the man, Lloyd Price (still going strong at 87) who, against the odds, has succeeded in so many different fields with his entrepreneurial skills.

Fellow New Orleans blues singer Archibald had an R&B chart hit with ‘Stack-A-Lee’ in 1950 and accused Lloyd of copying his rendition when the latter recorded ‘Stagger Lee’ in 1958. Undoubtedly Lloyd knew Archibald’s masterpiece and used it as a blueprint. You can hear it in the above Toppermost. (If you missed it, go back to Footnote 6 – you won’t be disappointed.) Dave mentions these details in this Toppermost and quotes a certain Cecil Brown who wrote the book ‘Stagolee Shot Billy’, in which he referred to Archibald as ‘Cox’. I’ve known of Archibald since the mid-1960’s and I’ve never seen him referred to as ‘Cox’. Dave is right to say, “quite where the ‘Cox’ came from I’m less sure”. I would go further and say I think Cecil Brown is mistaken. Archibald’s surname was Gross and he was sometimes called ‘Archie Boy’ but never ‘Cox’ in the scores of references to Archibald I’ve read over many years. There are several hundred references to Archibald Cox on Google. Besides the Brown’s book entry, though, there are only two other references to a musician Archibald Cox – both from recent books about the story of Stagger Lee and it seems likely that both used Brown’s book in their research. All the rest of the Archibald Cox entries refer to the Watergate lawyer who happened to be born in the same year (1912) as the blues singer Archibald (Gross) and became most famous in 1973, the same year the musician died. Does anyone else out there in Toppermost-land know of the blues singer Archibald being referred to as ‘Cox’?

Excellent again, Dave. Lloyd Price was still active in the early 70s. I picked up a small batch of 45s a few years ago all in one shop. Ready for Betty on President (1970) is lively but a tad generic. Then he did a version of Fair Weather’s UK hit, Natural Sinner. He was probably trying to get a US hit from it as it was Top Ten by Fair Weather. But he went to Muscle Shoals to do it, so his version (on Wand) is excellent. He did some work for the GSF label- Trying to Slip Away is outstanding. Electric Lover is classic early 70s funk. This is Northern Soul collectable rather than rock ‘n’ roll. He did a GSF album in 1972 “To The Roots and Back” where he did new stuff mixed with new versions of Lawdy Miss Clawdy, Stagger Lee and Personality. It’s one I keep an eye out for it, but it wasn’t released in the UK. I listened to the free 30 seconds and it’s kind of “Lawdy get down in the mornin! Yay! Miss Clawdy, y’all” which is a matter of taste. Here’s the 1972 version of Lawdy Miss Clawdy. Magnificent horns.

Personality is such a great single, and it’s the same guy who did Stagger Lee and Lawdy Miss Clawdy. Vale Lloyd Price.

David, the first thing that hit me when I started the research for Lloyd was the fact that he was still alive. Unlike so many of his peers. Maybe there was some inevitability about it; I always got the impression that Lloyd would pick himself up and dust himself down whatever life threw at him. With regard to Personality, I was wondering whether that song would get raised. But you did it very gently. I also have to concede that if the name Lloyd Price hits me for any reason, it’s Personality which is often first to play in that jukebox that I call my brain.