| Track | Album |

|---|---|

| Needles In The Camel’s Eye | Here Come The Warm Jets |

| Burning Airlines Give You So Much More | Taking Tiger Mountain… |

| Mother Whale Eyeless | Taking Tiger Mountain… |

| St. Elmo’s Fire | Another Green World |

| Big Day | Diamond Head |

| On Some Faraway Beach | Here Come The Warm Jets |

| Everything Merges With The Night | Another Green World |

| The Big Ship | Another Green World |

| Spider And I | Before And After Science |

| 1/1 | Ambient 1: Music For Airports |

Brian Eno playlist

Upon arriving on the music scene as part of Roxy Music in the early 1970s, Brian Eno made an unlikely candidate to become one of the most groundbreaking and respected musical figures of the past half-century. A self-professed non-musician, Eno’s contributions to Roxy largely involved twiddling knobs on the mixing board and adding askew keyboard sounds. He was probably better known at the time for his striking appearance, long hair and feathers and space-alien outfits, taking the glam look well beyond that of future collaborator David Bowie. Not unsurprisingly, Roxy frontman Bryan Ferry was displeased with the distraction, and after two albums Eno was out of the band.

This turned out for the best; instead of being buried behind the charismatic Ferry, Eno cobbled together four truly fantastic solo albums, a varied hodge-podge of glam and pop and prog and proto-new wave and electronic music; it’s this period from which our playlist today is drawn.

And then Eno just … stopped. Four amazing albums, and he was out of the game – or at least out of rock & roll. He turned his attention to ambient music, releasing decades of groundbreaking albums full of quietly introspective instrumentals ideal for creating musical backdrops. At the same time, Eno became a go-to producer, most notably with his significant contributions to the discographies of David Bowie and Talking Heads, as well as everyone from U2 to Devo to Ultravox and countless others. (And yes, a second Top 10 focused on Eno’s work as a producer/collaborator would be well worth the time.)

But enough history, let’s get to the mix.

During Eno’s brief run of rock-oriented music, largely encompassed on the four solo albums released between 1973 and 1977, two very different Enos emerge. On the one hand, you have the vocal rock songs, off-kilter and unique, yet still comfortably fitting in the space between Roxy Music’s forward-looking arty glam rock and Eno’s future work with Bowie and Talking Heads. On the other hand, you have his initial forays into ambient music, largely (but not entirely) instrumental, beautiful and soothing and meditative.

Needless to say, skittering between these two styles on a mix makes for a somewhat jarring experience. So what you see at the top of the page are really two self-contained Top 5 lists – five of Eno’s finest moments as a rock musician, followed by five beautiful pieces better suited to a quiet evening on the sofa.

We kick off with Needles In The Camel’s Eye, the opening track from Eno’s solo debut, 1973’s Here Come The Warm Jets. It’s a rollicking tour-de-force, as straightforward a rock & roll song as Eno could muster, while retaining Roxy’s glam bona fides. (Indeed, it was used as the backing for the opening credits in Todd Hayne’s Velvet Goldmine, a fictionalized faux-Bowie biopic/glam-rock love letter.) Somewhat surprisingly given his peripheral role in Roxy, Eno quickly establishes himself as both a creative songwriter and a distinctive vocalist. The balance of the debut is comprised largely of eclectic upbeat tracks, too odd for the mainstream but still highly catchy – Baby’s On Fire is darkly compelling, with a fierce guitar solo; while Cindy Tells Me is an almost sweet fifties-styled throwback, at least until the disorienting instrumental break kicks in. The album also includes a couple quieter tunes previewing what was to come, including the absolutely gorgeous piano-driven On Some Faraway Beach, the first hint that while he excelled at quirky rock songs, Eno also had a knack for evocative soundscapes.

Eno’s next album, 1974’s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), represented something of a continuation; while not a dramatic departure from the debut, the songs are more refined, the pop songs a little catchier and the quirkiness better integrated into some surprisingly solid songwriting. In my view, it’s Eno’s best ‘rock’ album, consistently entertaining, making it particularly hard to pick a favorite or two. I opted to include in the Top 10 the delightfully engaging Burning Airlines Give You So Much More as well as the slightly-askew pop of Mother Whale Eyeless, but other highlights include the raging glam-punk of Third Uncle (later covered by goth rockers Bauhaus) and the infectious The True Wheel. The album also closes with another gorgeous ballad, the quiet title track again previewing Eno’s ambient work.

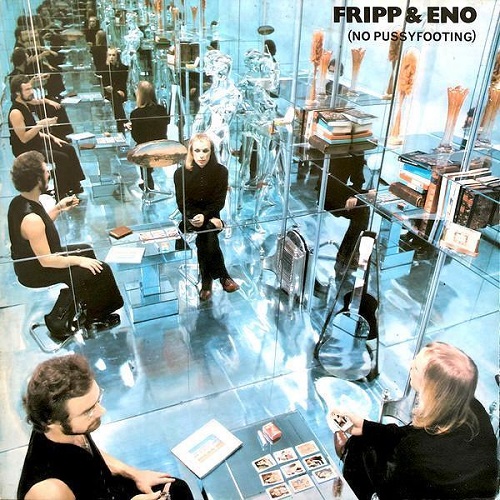

The real revolution occurred on his third solo album, 1975’s exquisite Another Green World, which introduces Eno’s ventures into ambient music. Which isn’t to say he doesn’t keep one toe in the water of rock music, most notably on the bewitching St. Elmo’s Fire (no, not the theme song from the horrific eighties film), a riveting swirl of odd percussion and synths, pierced with a face-melting guitar solo from frequent collaborator Robert Fripp (who had recently departed King Crimson). And the perky I’ll Come Running is a positively buoyant love song, guileless and charming.

But it’s the quiet, largely instrumental work on World that’s particularly attention-grabbing. I can’t say enough about what this album has meant in my own life – indeed, I recently published a music memoir which dedicates a whole chapter to Another Green World. I included just a small sampling of highlights on the playlist. Everything Merges With The Night, a meditative vocal number, is one of Eno’s loveliest ballads, the sort of thing to play as the sun sets, moody and haunting yet somehow reassuring. And the instrumental The Big Ship, a wash of intertwining synths that suggests something truly cosmic, is wondrously hypnotic, a song so cinematic in its sonics (despite its musical simplicity) that three different films in recent years have used it to soundtrack their closing moments. I’m an agnostic man, but I’ll say it here: when I let myself become enveloped by The Big Ship, I can almost believe there is some greater power in the universe. (It was painful for me to omit from the playlist the gorgeous Becalmed, a devastatingly soothing number that I have enlisted on countless occasions to fend off my bouts of chronic insomnia; if you, too, are in the market for a musical sedative, that’s the one for you.)

Eno’s final album from this period, 1977’s aptly-titled Before And After Science, is divided equally between frenetically upbeat new wave-ish offbeat rock and further ventures into quiet ambience. None of the rockers made the cut here, but check out the catchy Backwater, conveying such a comfort level with pop music that it’s shocking Eno left it all behind after this album; also great fun is King’s Lead Hat (an anagram of Talking Heads, with whom Eno felt an early kinship and whose finest work he would later produce). As with Another Green World, it’s the quieter moments here with which I’m particularly taken. The somber vocal tune Spider And I is a personal favorite, a hushed melody backing lyrics that evoke the lonely aftermath in some post-apocalyptic sci fi film. It’s a truly astounding work, and, alongside similarly gorgeous vocal ballads Julie With and By This River, a suitable send-off for Eno’s brief flirtation with rock (or rock-adjacent) music.

The tracklist above is rounded out with two tracks from outside this 4-album run. On the more upbeat side is Big Day, one of Eno’s catchiest, most pure-pop (yet still a tad quirky) tunes. It appears on an album from Roxy Music guitarist Phil Manzanera, 1975’s Diamond Head; Manzanera lent his guitars to (and co-wrote) several songs on Eno’s albums during this period, and here Eno repays the favor. And we wrap things up with 1/1, the opening track from 1978’s Ambient 1: Music For Airports, the first in a series of instrumental releases that followed Before And After Science. It’s a gentle, repetitive riff, random piano tinkling that runs on for over 17 minutes, less a song than a soundscape ideal for playing in the background at an art exposition or, yes, the airport terminal. These floating waves of sound obviously occupy a musical universe distinct from the preceding albums, but give a sense of what his solo work would sound like in the decades ahead – at least until he finally broke his (vocal) silence with his excellent 1990 collaboration with John Cale, the surprisingly pop-oriented Wrong Way Up.

EnoWeb: The Latest Brian Eno News and Information

More Dark Than Shark: a Brian Eno archive

Brian Eno biography (Apple Music)

Marc Fagel is a recovering lawyer living outside San Francisco with his wife and his obscenely oversized music collection. He is the author of the recently-published rock lover’s memoir “Jittery White Guy Music”. His daily ruminations on random albums in his collection can be seen on his blog of the same name, or by following him on twitter.

TopperPost #846

Thanks for this great piece Marc. Really enjoyed it and ‘Needles In The Camel’s Eye’ was like a time machine back to the 1970s. Thanks again.

Glad you enjoyed it!

Brilliant picks, and wonderful writing too. I actually wouldn’t argue with any of those choices, though the Diamond Head song is new to me it’s an instant favourite.

Thanks, Rob!

Enjoyed this … I remember seeing Eno with Roxy Music early on. Diamond Head is a fine album … Phil Manzanera used guest vocalists … Eno, Robert Wyatt, John Wetton. John Wetton’s thunderous bass line propels Big Day … and also Baby’s On Fire and Driving Me Backwards from ‘Here Come The Warm Jets’. The last two are Fripp on guitar, Wetton on bass, so two thirds of King Crimson at that point. (King Crimson, Roxy Music, Eno were all managed by EG at the time).